By John Richardson

THE EARLY DATA suggest that China’s polypropylene (PP) demand could grow by 3% in 2023. This would be in line with the base case forecast I provided in February.

I calculated the above estimate for 2023 by taking the January-February China Customs net import data and our estimate for local production during the same two months, divided by two and multiplied by 12.

This at first indicated demand growth this year of 6%, in line with consensus forecasts. But I heard from contacts that China’s powder-based PP plants – along with its other smaller and older PP facilities – were running at very low operating rates.

This led me to reduce our headline estimates for local production, resulting in my lower estimate of 3% growth, assuming low operating rates continue for the rest of the year.

Growth of 3% would leave this year’s demand at around 35.5m tonnes, some 900,000 tonnes more than last year. If demand grew by 6%, this would leave the market at 36.7m tonnes.

Hopefully, of course, I am wrong. But be prepared for 3% growth or even lower in 2023 because of China’s debt, demographic and export headwinds that I’ve flagged up on many occasions before.

Compare 3% to as recently as 2020 when demand grew by 10%, Average annual demand growth between 2000 and 2020 was also 10%.

And as the chart below reminds us, there has been no post zero-COVID recovery. I never thought this was likely because of the long-term structural challenges of demographics and debt, along with weaker exports.

The China CFR PP injection and block copolymer grade price spread over CFR Japan naphtha costs was just $264/tonne from 1 January until 7 April 2023. This was close to last year’s record low of $258/tonne since our price assessments began in 2023.

Let us put these recent spreads into important longer-term context: The average 2003-2020 annual spread was $571/tonne compared with the 2022-2023 average of $261/tonne.

As market participants continue to be misled by the significance of short-term price movements, I need to continue to stress the importance of spread analysis. Spreads over time reflect the real state of any petrochemicals market.

So, when people talk about “recovery” as short-term prices rebound, China’s average 2022-2023 spread would need to recover by 119% from where we are today to reach 2003-2020 average.

Only when we see a 119% recovery in spreads will there have been recovery. It is as simple as this.

Given the macroeconomic challenges and the extent of global oversupply, I see a 119% rise over the next 12-18 months as almost impossible.

The $64,000 question is, of course, this: When will spreads return to their long-term average? In my view, not before the second half of 2025, such is the length of global oversupply and the Chinese and global macroeconomic challenges.

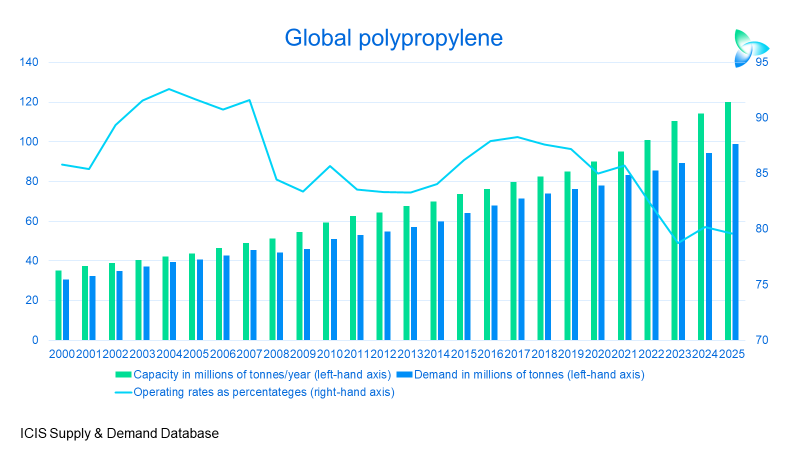

On global oversupply in 2023, the chart below is a sobering reminder of where we stand.

ICIS forecasts that global PP capacity will exceed demand by 21m tonnes this year and will stay at a 2023-2025 annual average of 21m tonnes. The 2000-2022 annual average of capacity exceeding demand was 8m tonnes.

Not surprisingly, as the operating rate line on the above chart illustrates, capacity utilisation is expected to be in a deep trough in 2023-2025. This would indicate weak profitability.

“Here you go again, pessimism, pessimism, pessimism,” I can imagine some people will say.

But in my view what we face today is the result of a lack of realism. This has involved a failure by the global PP industry to prepare for the inevitable, long term structural economic slowdown that had to happen in China.

Also, not enough people were expecting China to build so much new capacity.

The market will get better, as I shall discuss in later posts, perhaps sooner than is commonly expected.

A common view out there is that there will be no return to average long-term PP spreads in China until 2026 where, as mentioned, I see a recovery in 2025 as possible. But this is going to require substantial capacity rationalisation.

And please read the following three news articles to underline why I still see a very strong post zero-COVID economic recovery unlikely:

- China’s exports were down by 6.8% year-on-year in dollar terms in January-February 2023, with the excess supply of containers a further indication of the weak export trade, according to this April 5 Nikkei Asia article. High inflation overseas will continue to act as a drag on China’s export trade during the rest of 2023, I fear.

- But in contrast, Reuters wrote in this 11 April article: “China’s consumer inflation hit an 18-month low and factory-gate price declines sped up in March as demand stayed persistently weak, shoring up the case for policymakers to take more steps to support the uneven economic recovery.”

- China’s policymakers might be able to encourage more consumer spending, despite the end of the real-estate bubble and China’s very worrying demographics that are pushing-up savings rates to meet pension and healthcare costs. But spending a lot more on infrastructure, as this 28 March New York Times article reminds us, could be difficult because of the extent of local government debts – and because most of the bridges and roads etc. China needs to build have already been built.

Again, don’t get me wrong here. As I’ve been stressing, China’s economic activity might well pick up later this year as, during zero-COVID it was as if China ‘s economy was travelling at 30 kilometres an hour.

The economy will likely return to, say 70km/h. But it can never return to 100km/h, and 70km/h is simply not fast enough to absorb the oversupply in the global PP business over the next 12-18 months.