By John Richardson

IN THE GOOD OLD DAYS, life was simple. Pretty much all that petrochemical and polymer producers had to do to be successful was to repeatedly add capacity in the secure knowledge that demand would always be sufficient.

Such was the comfort of the good times that whenever a brief downturn happened, talk of capacity closures of less efficient, older plants ended up being mainly only talk.

Supposedly disadvantaged producers were very grateful they hadn’t listened to some of the experts, as industry-wide margins quickly bounced back following the brief downturns that characterised the golden years of 2000-2021.

Europe also made a nonsense of the broad-brush view that because it had very old steam crackers and polymer plants, a big wave of shutdowns had to happen.

European crackers have been made more efficient through additions of new furnaces and through the better capture and recycling of heat that, of course, equals energy.

Greater feedstock flexibility has been added, with plants in Northwest Europe also connected through extensive ethylene and propylene pipeline systems.

“I would rather have a good propylene supply contract than a bad steam cracker,” commented a sales executive with a major European polypropylene (PP) producer in 2017, whose company’s PP plant was connected to the Northwest Europe propylene pipeline system.

But as I also discuss later in the post, there is another operating efficiency not that needs to be built into plants in Europe and elsewhere and this is carbon-reduction technologies.

The jury is out on whether it will be worthwhile building in these efficiencies to some of the older plants, given the scale of today’s downturn – and because of investments in new low carbon crackers due to start-up from 2026 onwards.

Asian producers have always had a higher cost base than Europe because of weaker integration with refineries (a lot of naphtha and other feedstocks from refineries are imported by Asia) – and because of less extensive pipeline systems.

But supposedly sub-optimal cracker complexes in Asia managed to survive previous downturns because of the China demand boom.

Even though other regions were not as directly shaped by events in China, the country’s extraordinary growth over the last 20 years made the overall petrochemicals pie an awful lot bigger than would otherwise have been the case.

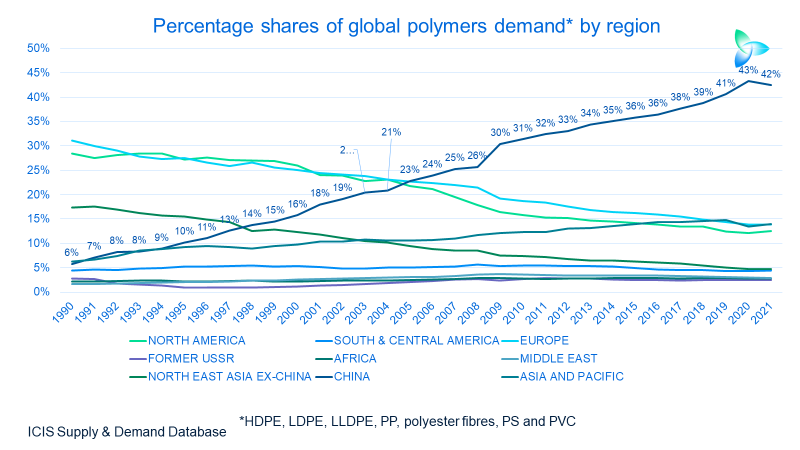

The chart below is a reminder of the extent to which we have become dependent on China for driving global consumption, going right back to 1990.

But it was from 2000 onwards that China’s growth really accelerated. This was thanks to its admission to China’s World Trade Organisation in late 2001 and China’s launch of the world’s biggest-ever economic stimulus package in 2009.

China’s demographic challenges

Now, though, there is a growing recognition that China has entered a long-term structural economic slowdown, thereby meaning lower petrochemicals growth.

Those who argue that this doesn’t matter because China’s base of petrochemicals demand is so much bigger than it was 30 years ago sometimes overlook the big shift in growth forecasts.

As recently as 2019, some observers were predicting mid -to high single digit-demand growth in China each year until 2040, in the same seven synthetic resins listed in the above chart.

As the slide below shows, ICIS expects average annual growth of just 2% for the same seven resins in 2023-2040. This would compare with actual average annual growth of 8% in 2000-2022.

Lower China growth forecasts are the result of the country’s demographic crisis and the end of its debt bubble.

I think it is fair to call this a demographic crisis. No country the size of China, and at its stage of economic development, has previously faced such a rapidly ageing population.

Will China find a way out of the crisis? To some extent, maybe, but the levels of petrochemicals demand growth being forecast are more typical of a fully developed economy.

Those who claim that the rest of the developing world can take up the strain of weaker China growth should get their Excel sheets out and spend more time on our excellent ICIS Supply & Demand Database.

The database tells us this: No matter how much you can feasibly increase growth rates in Africa, Asia and Pacific and Latin America versus our base-cases, this will still not make up for Chinese polymer demand growing at 2% per annum versus earlier higher forecasts.

The core point is that the global polymers market will be a lot smaller than people had previously estimated because of events in China.

And as I’ve been highlighting since 2014, China is making more of its own petrochemicals and polymers because of a government-supported self-sufficiency drive.

Sustainability is the way forward, but it won’t be easy

There are two other changes in this downcycle versus previous downcycles: The greater pressure on petrochemicals to decarbonise and to do its share (whatever that share should be) of reducing plastic waste.

The implications of these sustainability challenges are so complex that it would be silly to attempt to cover them in one blog post. But suffice to say to say here, I believe there will be no “one size fits all” new business model for our industry.

I expect we will see a hybrid model of some “local-for-local” producers who run on recycled feedstocks, along with “old-style” cracker complexes that continue to run on traditional hydrocarbon raw materials.

But all types of plants will need to be highly carbon efficient through technologies such as electric furnaces, grey hydrogen and green hydrogen.

Will the petrochemicals industry be able to realise its ambition of creating large volumes of new demand by reducing carbon output in other industries?

A lot of R&D work needs to happen first, followed by persuasion or marketing, before petrochemicals can play a leading role in what is called the Materials Transition -using materials such as polymers to reduce carbon in the atmosphere.

We must also bear in mind the parallel efforts of other industries to decarbonise, such as in construction.

But new approaches must happen because we can no longer rely on China to effectively bankroll our industry – and because of the demographic, environmental and geopolitical challenges to economic growth elsewhere.

And given the risks that global GDP growth will be severely constrained by all the above, it is hard to conceive of any new approaches that are not centred on decarbonisation and dealing with plastic waste.

(For more information on decarbonisation and petrochemicals, see this excellent ICIS Insight article from my ICIS colleague, Nigel Davis).

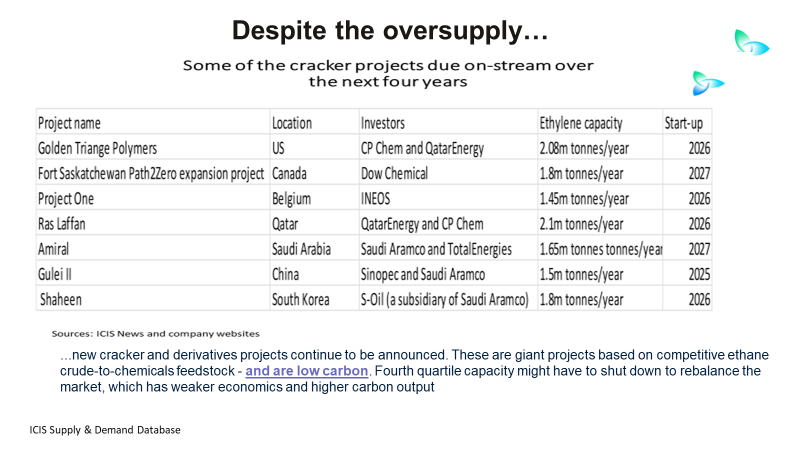

Switching themes, a sober reminder of where we are today is the chart below.

This outcome is not just because project proponents misread China. Oversupply is also the result of disappointing growth in the rest of the developing world because of the pandemic, and more recently due to the impact on global growth of higher interest rates.

But I see a misreading of China as the main driver of the record levels of oversupply.

Conclusion: Step One could be major consolidation

Supply must, of course, meet demand. Markets need to balance out. As the extent of red ink becomes clear in financial results, I see the pressure for consolidation building.

“It is very hard to close a cracker down because of the links to upstream refining etc. But I do see more shutdowns taking place than in previous downturns,” said a source with a global petrochemical producer.

“It is not just the weak economies of scale that will force closures, but also the cost of decarbonising assets,” he added.

“The cost of decarbonisation will not be worth it for smaller, older plants. Shutting the plants might also be more feasible this time around because associated refineries have shorter lifespans due to electrification of transportation,” said the source.

This makes sense to me.

Further – as I discussed in January and as the slide below reminds us – a new breed of very big and carbon efficient crackers is scheduled to come on-stream from 2026 onwards. This could place more pressure on older, less efficient crackers.

Step One of moving towards a new business model could therefore be more consolidation than we have seen in previous downturns.

The speed of closures seems likely to shape how quickly markets balance out, as I don’t see the challenges to demand getting any easier. I see the end of this downcycle as being no earlier than 2025.

The carbon efficiency of petrochemicals will also, hopefully, improve as less carbon efficient plants are shut down.

Steps Two and onwards will be the subject of further blog posts and in ICIS news and ICB article as we discuss all the complexities surrounding decarbonisation at petrochemical plants, the Materials Transition and reducing plastic waste. Watch this space.