By John Richardson

THE OLD MINDSET is still, in my view, holding us back which is this: The worst conditions get in the Chinese economy, the better they will soon become.

Too many people I am speaking to, and too much analysis I am reading, assumes that all the Chinese government needs to do to return the heady old days of high growth is turn on the stimulus spigot.

This thinking was in evidence yesterday as stock markets rallied and sentiment improved in petrochemicals markets following the announcement of a 20-point government plan for stimulating the economy. The release of the plan came after more disappointing purchasing managers’ indices.

Sure, as I keep stressing, petrochemicals markets might improve during H2 this year. But they have a huge distance to travel before China spreads and northeast Asian margins in the key polyolefins market return to their historic averages.

Without the context of spreads and margins, short-term price movements, up or down, tell us little.

And based on the data, as the data is the thing, I feel it reasonable to conclude the following (this is from my 20 July post):

The phrase “pushing on a piece of string” might best describe the logic behind calls for another round of big economic stimulus in China. Any extra money pumped into the economy could be largely saved rather than spent because of weak consumer confidence resulting from an ageing population and the end of the property bubble.

This is assuming that China has the wiggle room for big stimulus given the scale of its debts. Furthermore, we cannot be sure if it has the appetite or not for further big stimulus because it is attempting to build a new economic growth model.

A “What if?” scenario where consensus opinion got China right

The ICIS data on polypropylene (PP) serve as an example of how wrong the market consensus thinking on China was just a few years ago, when today’s big wave of new capacity was being planned.

Let me start with what our base case is telling us about global supply and demand. Note that I have redacted the demand and supply numbers. If you are need the data, contact me at john.richardson@icis.com.

Average annual PP capacity exceeding demand was 7m tonnes in 2000-2019 with the global operating rate at 87%. But average annual capacity exceeding demand is forecast to be 21m tonnes in 2020-2030 with the operating rate at 80%.

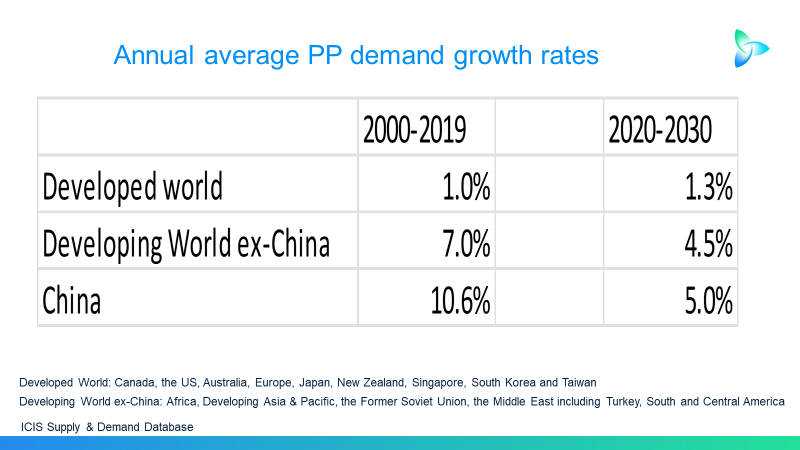

See the chart below showing the ICIS actual average demand growth rates for the three mega-regions in 2000-2019 versus our forecasts for 2020-2030.

I chose 2019 as the dividing line because this was of course the year before the pandemic.

Our lower forecast growth rate for the Developing World ex-China to some extent reflects a sharp fall in consumption in 2020 and 2021. But we see Developed World demand ticking up slightly from the historic average in the 2020-2030 forecast period.

The biggest projected fall is, as you can see, in China’s annual average growth rate from 10.6% in 2000-2019 to 5% in 2020-2030.

The big change in China’s growth trajectory occurred in late 2021 with the launch of the Common Prosperity policy pivot and the end of the real estate bubble.

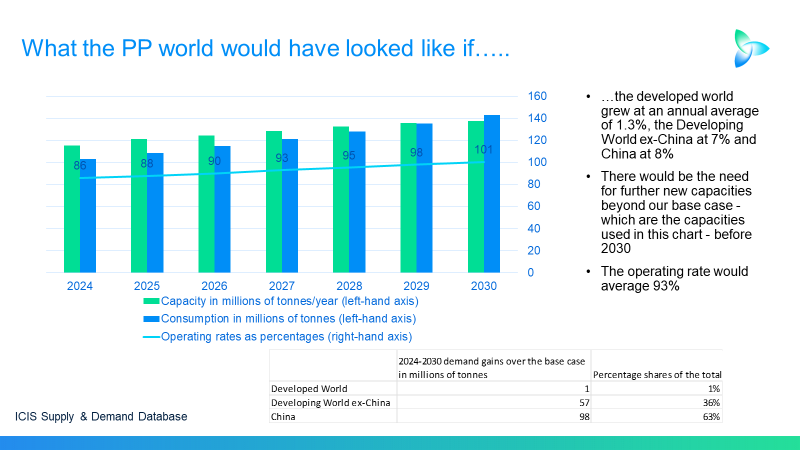

Let’s imagine, for argument’s sake, that the Developing World ex-China’s annual average growth between 2024 and 2030 was 7%, as in 2000-2019. The region’s growth this year is forecast to be around 5% and we are too close to the end of this year to reinvent what has almost become history.

Likewise with China, its PP growth looks set to be around 1% this year, so let’s stick with this as a realistic starting point.

But in 2024-2030, let’s assume China grows at 8% per annum demand – in line with the old consensus forecasts.

I’ve raised Developed World demand growth to 1.3% from 1% in 2024-2030. But I’ve left the ICIS forecast for growth of 1% in 2023 unchanged for this region.

The results are quite extraordinary as the chart below tells us.

The average global operating rate for 2024-2030 would be 93% and surpassing 100% in 2030. This would likely lead to capacity additions beyond our base case (represented by the blue bars) before 2030.

Now let us examine the table at the bottom of the chart. It shows that global demand in 2024-2030 would be a cumulative 155m tonnes more than our base case. China would account for 98m tonnes – 63% of the total.

But in my view, such an outcome for China growth is simply impossible.

How to get back to the historic operating rate of 87%

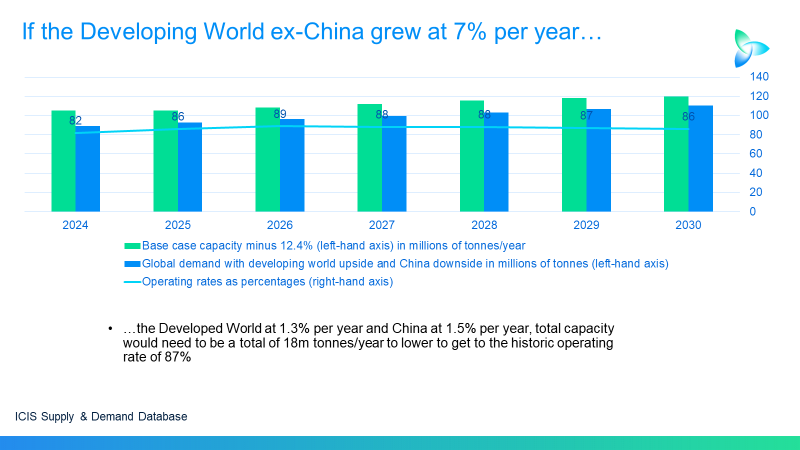

Using our base case for the global PP supply and demand balance in 2024 as a starting point, what would it take to get back to the long-term historic global operating rate of 87%? Note that we see the 2024-2030 operating rate falling to just 78%.

The blue bars represent what capacity would look like in millions of tonnes if it were lowered by an average 8.7% per year from our base case between 2024 until 2030. This would amount to capacity at a total of 8m tonnes/year capacity across all the years lower than our base case.

But our base case forecasts for China’s demand growth should be just one of your scenarios. As mentioned, we are forecasting China growth of 5% per year in 2020-2030. The forecast for 2024-2030 is also 5%.

As the chart below reminds us, China’s PP demand growth (and it the same for all the other petrochemicals and polymers) has grown in per capita terms – and in millions of tonnes – way, way out of proportion to the size of its population.

The concept of “dematerialisation” involving China’s annual demand growth falling to single digits – or even turning negative – is being discussed.

This is because of the three events detailed in the above chart have become history, as China faces the challenges of a rapidly ageing population, the end of debt-fuelled growth and increased geopolitical tensions with the US.

So, why not use the chart below as a downside scenario? Here, I assume the higher growth rates of 7% per year for the Developing World ex-China and 1.3% for the Developed World. But I took China’s annual average growth down to just 1.5%.

In these circumstances, global capacity would need to be an average 12.4% lower per year lower than our base case in 2024-2030 to return the operating rate to the historic average of 87%. Capacity would need to be a total of 18m tonnes/year lower during this period.

Consensus: Why lower growth should be a cause for optimism

Global PP demand general seems likely to suffer from the growing disruption to economies caused by climate change.

So much, perhaps for the suggested upsides for Developing World ex-China and Developed World growth detailed above as China’s long-term structural economic slowdown continues.

What could these outcomes mean for global PP capacity versus demand in 2024-2030? Again, contact me for the data.

I am often accused of pessimism. But I see lower growth as a positive for reasons I discussed in my 18 June post:

The petrochemicals world has changed irrevocably, I believe. But this is a good thing as the absence of the kind of easy volume growth we’ve seen in the past will better preserve the environment. And the future for our industry lies in environmental protection and restoration, through the approach of treating sustainability as a service.