By John Richardson

ONE OF THE MISTAKES being made out there is viewing the energy and chemicals transitions (two different but also connected challenges) as separate from core chemicals businesses.

This is much as an error as assuming that the traditional chemicals business isn’t being reshaped by ageing populations in most of the world, the effects of climate change on economic growth, the end of China’s “economic miracle”, downward pressure on consumption exerted by environmental concerns, artificial intelligence and much more volatile geopolitics.

All the above are reshaping our industry in such profound ways that we could well be seeing the death of traditional down- and upcycles, as I discussed last Friday when I suggested that global chemicals demand might have peaked.

What if, as I discussed on Friday, we already have more than enough commodity capacity to serve tomorrow’s demand?

Sure, the feedstock-advantaged Middle East and the US may continue to build basic chemicals plants to take larger slices of a diminishing pie of demand. Both regions have the feedstock advantages to do this.

In Saudi Arabia, turning more oil into chemicals might also happen because of the threat posed to oil production by electrification of transport.

And China may continue to push hard towards complete chemicals self-sufficiency – provided it can find sufficient feedstocks at the right price – for supply security reasons in an ever-more uncertain geopolitical world.

This means that nobody else would, under this scenario, be able to build commodity chemicals capacity.

In fact, plants may well have to shut down in Europe, South Korea, Singapore, Japan, and possibly also Southeast Asia, to make space for new capacities in the Middle East, the US and China – and to try and redress today’s all-time low operating rates.

In Europe, South Korea and Japan etc., some companies could reach the conclusion that as the world is awash with basic chemicals, they are better exiting basic chemicals and polymers altogether, replacing their production with imports.

This is where the links to sustainability come in. Producers in Europe, South Korea and Japan etc. could import basic chemicals and polymers at costs lower than maintaining loss-making assets, while differentiating themselves downstream in higher-value lower carbon and circular chemicals and polymers.

In a world of carbon taxes, carbon trading schemes, carbon import barriers and recycling targets in developed economies, this is a new path to competitive advantage.

Higher-value or speciality chemicals are by their nature smaller in volume than commodities. If you produce too much of a speciality then of course, as history has shown us, it becomes a commodity.

The chemicals companies that survived a great shake-out in Europe, South Korea and Japan etc. would thus be smaller than today, more niche.

“But hold on.” I can again here you say, “What about the links to upstream refineries? This can make it hard to shut down associated commodity chemicals plants.”

Absolutely. In some cases, a small naphtha cracker linked to equally uncompetitive downstream commodity polymer plants might limp on because the local refinery needs to find a home for stranded inland naphtha.

If a home isn’t found for the naphtha, the upstream refinery, important for local gasoline and diesel supplies, might have to close.

And s electrification of transport gathers pace in Europe, refineries could have cheaper chemicals feedstock to get rid over the medium-term. But electrification will surely eventually cause the closure of refineries, making chemicals shutdown decisions easier.

Are fractured logistics chains also a New Normal? There was the pandemic and now the Red Sea crisis. In this volatile world of geopolitics, we should consider permanent global supply chain disruptions.

Converters in Europe are now said to be demanding big discounts on commodity polymer imports from the Middle East and South Korea because of the much-longer shipping times and uncertain arrival dates. The discounts are reported to have made some exports to Europe inviable.

But I see this problem as easy to fix. Overseas suppliers just need to invest more in local warehouses that would hold back-up stocks.

And for the standalone chemicals companies with no links to refining, the transition to a niche business model is obviously easier.

Japan is already travelling down this path

Effective partnerships with governments will be important for success if this becomes a global direction of travel.

Where regulations are inconsistent, confusing and contradictory, and if political priorities keep shifting, chemicals companies are going to find the sustainability transition very difficult.

Japan has long been an example of a country with an effective partnership between its government and its chemicals industry.

The old partnership was based on building commodities chemicals capacity to serve the country’s vast downstream manufacturing industries.

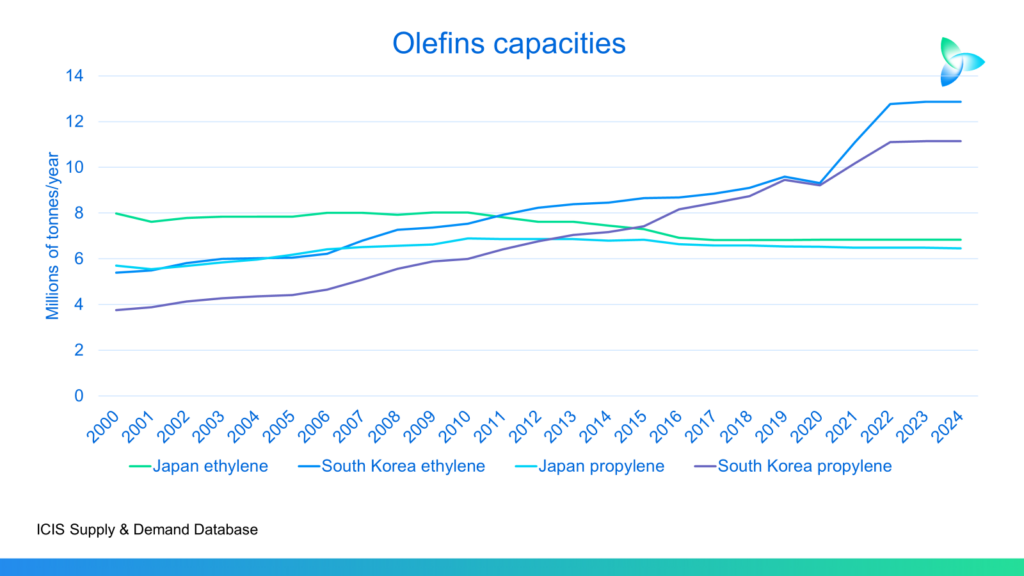

But as the chart below from the ICIS Supply & Demand Database shows, Japan’s ethylene and propylene capacities have declined since 2000. Contrast this with South Korea, the subject of a future blog post, where capacities have expanded to feed a major increase in exports of downstream commodities.

Japan has a very small commodity chemicals export exposure because of the average of age of its crackers (70% of its ethylene capacity is 50 years old), the small scale of its plants and feedstock disadvantages.

“Lots of Japanese polymer capacity has shut down, for example in polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and paraxylene (PX),” said my ICIS colleague, Itaru Kudose, in this 25 July ICIS Think Tank podcast.

He added that consolidation in Japan accelerated 1-2 years ago, as was the case in Europe, as energy costs increased and because of global chemicals oversupply.

Japan is increasingly focusing on speciality chemicals and polymers and polymer compounding where Japan is leading player.

The EU has proposed a target that the region’s automakers should use 25% recycled plastics in their vehicles by 2030. Japan, which has a big presence in compounding in Europe, is thus working on innovations to help hit this target.

“Japan is among a group of 136 countries that have pledged climate commitments to reach net zero by 2050,” wrote the World Economic Forum in this January 2023 article.

The Japanese government’s decarbonisation push for the chemicals industry included replacing natural gas and off-gases with ammonia to heat-up steam crackers, Itaru added in the same podcast.

He said that electric crackers or “e-crackers” that run on renewable energy were viewed as too expensive, both in Japan and South Korea.

The Japanese government was also encouraging the use of bio-naphtha and pyrolysis oil as cracker feeds to reduce carbon, with pyrolysis oil of course improving circularity as it is produced from plastic waste, he added.

Japan had adopted the International Sustainability and Carbon Certification (ISCC) mass balance approach to support the switch to renewable feedstocks, said Itaru.

But given that it was estimated that only 5-6% of Japanese cracker feedstocks could come from bio-naphtha and pyrolysis oil, decarbonisation efforts also included carbon capture and storage (CCS), he added.

There were ambitious plans to turn Japan into hydrogen economy to reduce liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports, Itaru continued. Japan was the world’s second-biggest LNG importer in 2023.

Returning to chemicals, he said that the Japanese strategy was to export higher-value chemicals and polymers, and to license new higher-value chemicals technologies, while increasingly importing the “simpler” products from overseas.

But any commodity imports would likely have to clear carbon import tariffs as Japan was planning introduce tariffs along with a local carbon credits trading scheme, said Itaru.

This might give Saudi Arabia an advantage in exporting to China given that it has ambitious plans for decarbonising its chemicals industry through CCS and electric furnaces powered by renewable energy.

The same could apply to the EU where a carbon border adjustment mechanism could be introduced for imports of organic chemicals and polymers from 2030. This would provide some protection for local producers who need to buy carbon credits under the EU’s carbon trading system.

Conclusion: Don’t put your sustainability team in a broom cupboard

It might be tempting to put sustainability in the corporate equivalent of a broom cupboard in the basement of HQ, beyond a few nice slogans on your website, because profits in green and circular chemicals are today hard to achieve.

Don’t make the same mistake if you are one of the potential Losers in the new commodity chemicals world as sustainability is a route to differentiation and survival.

And please, again, don’t make the mistake of assuming that this is just another downcycle. The evidence instead points to a fundamental realignment of the chemicals industry.

If you think otherwise, you must believe that the chemicals industry is divorced from the rest the world when, of course, it isn’t.