By John Richardson

WE EXPECT China’s PP demand to rise by 6.5% in 2018 to total consumption of 27.8m tonnes. We then expect a further increase of 6% to 29.3m tonnes next year.

It is too early to say for certain, but there is a risk that 2018 and 2019 PP demand growth will be less than we forecast for the reasons we explain below.

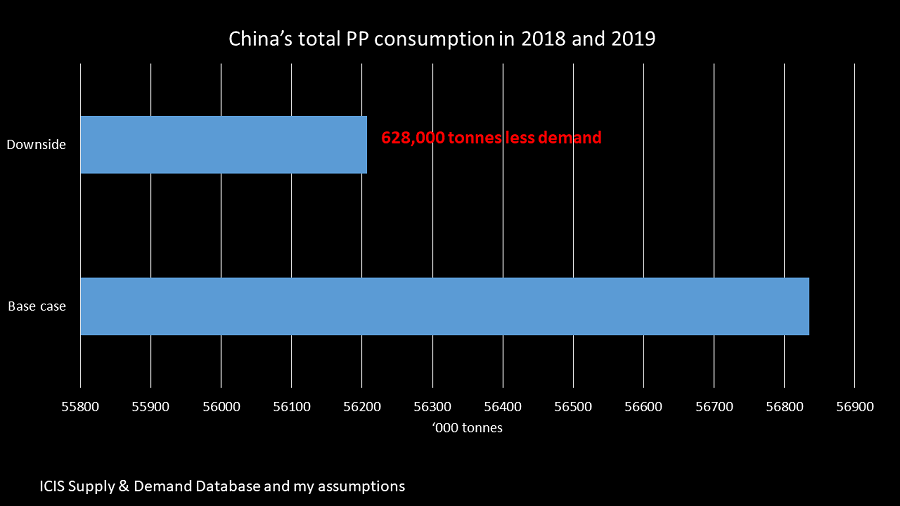

Take just half a percentage point of this year’s forecast growth and 2019 and this a cumulative loss of 628,000 tonnes of demand.

My downside assumption is pure guesswork and may well be wrong. But it does show the scale of the risks ahead as a result of decelerating Chinese credit availability in the environmental of a US/China trade war.

How economic stimulus distorts demand

The problem with excessive economic stimulus, and with it of course debt, is that it brings forward future consumption.

The new car that, for instance, you might otherwise buy next year you buy this year because the low interest financing deal is just too good to resist. Or you might not have otherwise been able to afford the car at all if it wasn’t for cheap lending.

And the difficulty is that when stimulus is withdrawn, discretionary spending on big ticket items such as autos declines.

In China, auto sales have fallen for three consecutive months as Paul Hodges discusses in detail in his latest PH report.

There is a very close correlation between the ebb and flow of China’s Total Social Financing (TSF) – i.e. the availability of credit in China – and the strength of auto sales. The greater the lending the higher the level of car sales and vice versa.

The TSF data for January-September 2018 should be available very shortly. But what we already know is that on a year-on-year basis in January-August, TSF –which is lending by both China’s shadow or private banks and its state-run lenders – was down by $224bn.

Lending via the high risk shadow banks was no less than $630bn lower, taking it back to the level before 2009. Why this year is so important is that it marked the beginning of the Chinese government’s economic stimulus programme, which was the world’s biggest-ever stimulus programme.

I can hear you say, “But hold on, what about the rise of China’s middle classes – the extraordinary rise in income levels as China has become richer? Isn’t this the real driver of strong growth in demand for autos and other consumer goods rather than economic stimulus?”

No. As the China Daily reports, Shanghai and Beijing are the only two places in the country where per capita disposable personal income surpassed 30,000 yuan in the January-June 2018, with the former recording 32,612 yuan ($4,777) and the latter 31,079 yuan. These are China’s two richest administrative regions.

In the same period, China’s average per capita disposable income grew 6.6% year-on-year in real terms to 14,063 yuan (just $2,303), according to the government’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

With disposable income still so low in China, despite decades of breakneck GDP growth, debt simply must have played a huge role in boosting short term demand for consumer goods.

This debt has not just led to cheap consumer loans. It has also led to long-running inflation in real estate prices.

Many Chinese who have sold second, third or more properties are sitting on great individual personal wealth. But an equal if not greater number are highly leveraged and are sitting on paper real estate gains only. A correction in house prices remains a major risk.

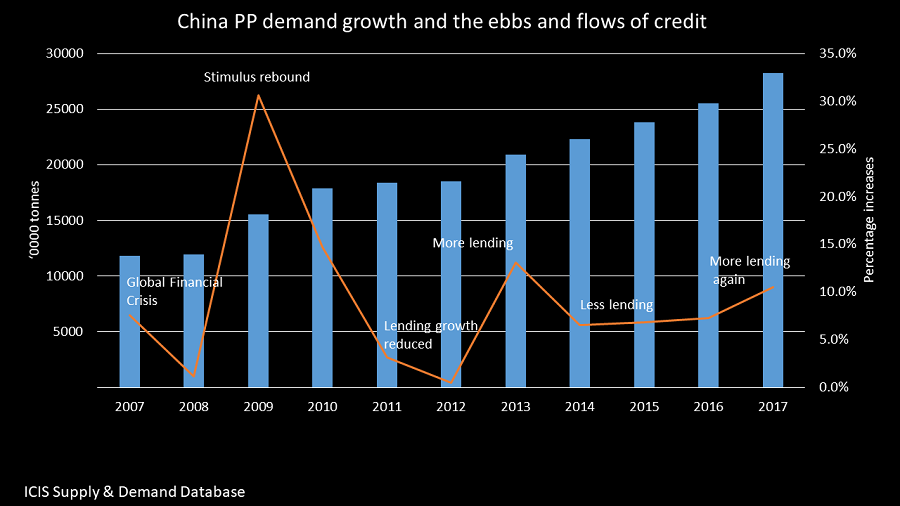

Now take a look at the chart at the above chart that shows China’s PP consumption growth. As with auto sales, PP’s consumption growth has risen, fallen and risen again since 2008 on the availability of lending. And of course there is an important link here as PP is heavily used to manufacture auto components such as bumpers, cladding, exterior trims, dashboards and carpet fibres.

China’s renewed stimulus in the right context

If you are a PP producer, you might therefore hope that yet another wave of economic stimulus in China will bring forward more demand from tomorrow – even if in the long term this creates further debt problems.

Earlier this month, China lowered the reserve requirement of its state-owned banks. This is the percentage of money that the banks have to hold in reserve against their loans. The lower the percentage, the greater the ability to lend. This measure is expected to inject $109bn of extra liquidity into the Chinese economy.

But you have to put this renewed stimulus into the context of what else is happening with the global economy – most obviously starting with the trade war.

US import tariffs on Chinese goods heavily target plastic products. Products affected include auto components, plastic tubes, pipes and hoses, plates, sheets, films, containers, bags and sacks, lids and caps and wall, ceiling and floor coverings.

China plastics industry players forecast that 2.6m tonnes of annual Chinese plastic products demand will be lost as a result of the tariffs. Sixty seven percent of plastics products demand is accounted for by products made from PP and PE.

And as Reuters reports, the Chinese tariffs on US imports are contributing to a rise in inflation in China. China’s consumer inflation accelerated for the fourth straight month in September, up 2.5% year-over-year to hit a seven-month high, according to the NBS.

Cost of living pressures may ease over the next few months because of a seasonal drop in vegetable prices. But the trade war seems likely to accelerate in 2019, leading to more tariff-driven inflationary pressure.

Adding to the inflationary pressure is the long-term trend of higher wages in eastern coastal provinces. Wages continue to rise as China’s population ages and its working-age population shrinks.

“But hold on,” I can again here you saying, ‘don’t these higher income levels mean more consumer spending power?”

Yes, but we must put income levels into the right context. IMF data show that Beijing and Shanghai incomes averaged $19,895 in and $19,450 in 2017. The average national income was $8,836.

These income levels are much higher than a decade ago. But they still remain low by Western standards and thus further underline the role that economic stimulus and debt must have played in boosting Chinese consumer spending.

No repeat of China’s global economic rescue act

The global petchems industry should be immensely grateful to the Chinese government as should every other industry. Its economic stimulus since 2009 has been the principal driver of global consumption growth in petchems and in finished goods.

To use PP as an example again, between 2000 and 2008, China accounted for 40% of global demand growth. This rose to 50% in 2009-2017. In autos, the latest PH report adds that if you take China out of the picture, January-May 2018 global auto sales were only 4% higher than in 2007.

Can China do it again? If it’s GDP growth starts to retreat by too much in 2019, will it go for a 2009 style stimulus package? Not without major financial risk, according to S&P. The ratings agency warns a “debt iceberg with titanic credit risks” because of a boom in government infrastructure spending.

So no, China very probably cannot afford to repeat its 2009 global economic rescue act.