THE CHEMICALS industry is the “industry of industries” – upstream of all the manufacturing chains. This is why what is happening in chemicals serves as such an important early indicator.

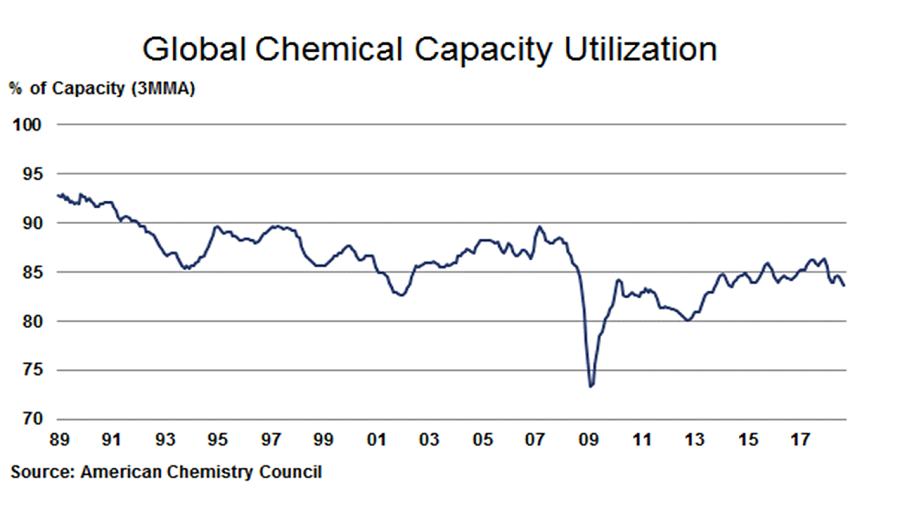

Take a look at the above chart – the latest from the American Chemistry Council. It shows that during September, capacity utilisation in the global chemicals industry fell by 0.3 points to 83.7%. This is down from 85.7% last September and below the long-term (1987-2017) average of 86.5%.

Evidence of where we are heading next comes from profit warnings by PPG and Trinseo, two US chemicals companies. Robert Patterson, CEO of US plastics compounder and distributor PolyOne also said in a third quarter conference call:

“What was new this quarter and really happened just in September was a slowdown in demand in certain North America end markets such as building and construction, and appliance, as well as in Asia.”

“The demand slowdown was abrupt, with certain customers delaying orders at the end of the quarter. They are citing concerns over tariffs, rising input costs, and weaker consumer demand as the primary drivers.”

He added that the Asian slowdown was, not surprisingly, centred on China.

What happens next?

No more spirit of central bank cooperation

The Chinese “put option” that allowed investment without fear for many years no longer holds. This was the knowledge that whenever a downturn occurred, the Chinese government would have enough financial muscle to re-stimulate the economy back to normal.

In a further indication of the scale of today’s financial challenges for the government, Caixin reports that Chinese companies have pledged a staggering Yuan 4.5 trillion ($0.65 trillion) worth of shares, a quarter of all free float shares, as collateral against loans.

The concern is that shares worth close to Yuan 900 billion have been pledged on loans where bankers are close to the point of requiring borrowers to top up their security.

If this happens then margin calls could cause a further collapse in Chinese equities. This would require a government rescue package on a very, very big scale that might well be unaffordable. An S&P report published last weekhighlighted the scale of existing Chinese government debt.

The stock market is only a small part of the problem. The bigger issue for China is the trade war that’s dampening its export earnings.

A comparison with 2008 is also important. Even supposing that China can afford a stimulus package on the scale of package after the Global Financial Crisis, the international climate is very different.

At that time there was a spirit of cooperation where central bankers in the US, the EU, the UK and Japan worked together to mitigate the impact.

This time around the animus between the US and many of its trading partners is one difference. So are other economic and political priorities of the EU, including the row over the Italian budget and the possibility that Britain could crash out Europe next March with no BREXIT deal.

US government debt maturity too short term

In the US, the problem is again debt. Last year’s tax cuts, which predominantly benefited higher earners, have inflated US the government deficit.

Republicans argue that the tax cuts will be paid for by strong GDP growth.

But Steven Ricchiuto Mizuho Securities was quoted in the FT as saying: “Identifying the macroeconomic impact of the Trump/GOP tax cut is fairly elusive, while the effect on the budget deficit is clear as day.

“The deterioration in the deficit is expected to increase in fiscal year 2019 as the deficit is seen as increasing to the $1t trillion level.

“A somewhat slower economy and additional Fed rate hikes, along with the remaining year-over-year revenue losses due to the tax cut, [will] likely ensure the deficit will be wider.”

This same FT article points out as US funding needs increase, China, the biggest us creditor, doesn’t have to sell down US Treasuries to cause a sharp spike in interest rates (selling down Treasuries by China would probably be self-defeating).

All that China has to instead do is buy less Treasuries than it has been buying to force a sharper-than-anticipated rise in borrowing costs. Because of China’s own economic issues and the US-China trade/Cold War, it is hard to see why China would buy more US government debt.

Another problem is that most Treasury debt matures in less five years, making the US very exposed to higher long-term rates. By comparison, the UK has been more cautious with its average debt maturity at 14 years.

The chart below illustrates this point. It also shows that the crunch time for US government funding will occur in a year’s time. But financial and commodity markets may well price in this funding crisis before it arrives.

The other threat to the rather rosy assumption that the US can grow its way out of debt problems is the damage caused to emerging markets by higher US interest rates and a stronger dollar. This has the potential to further hurt US export earnings if the dollar further strengthens on a flight to safety.

Plus, of course, further weakness in emerging markets – including most importantly China – would be bad news for chemicals demand, as it is the emerging markets that drive global growth in demand.

And in terms of tonnes consumed, China is the biggest global consumer in the four key steam cracker derivatives – PE, PP, styrene and ethylene glycols.

It is time for chemicals companies to get on with their recession planning.