By John Richardson

WHAT if the number of new vehicle sales in China reached a long term peak of 28.9m in 2017? What if the declines in sales that we saw in 2018 continue or that at the very best sales remain flat?

“Let’s put this in perspective, though. Just look at how the market has grown. Even with 2018 sales down by 2.3% at 28.1m, sales were just 9.3m in 2008. This tells us that even if future sales were flat or declining, the market would remain a lot bigger than 11 years ago,” you might well argue.

This is of course true. But the problem is expectations. The auto manufacturers and the chemicals and polymer companies that supply them with raw materials assume that China’s auto ownership will continue to grow towards Western levels per 1,000 people. In the US, there are 910 vehicles per a 1,000 people whereas last year in China the number was still at 166. Auto and chemicals companies have invested in new capacities on this basis.

But consider this: What if more and more of these vehicles are second hand? Fellow blogger Paul Hodges has long argued that the second-hand car market in China is nascent and has tremendous room for growth. In his latest PH report, due out shortly, he contends that in poorer inland areas of China it makes every bit of sense to grow the second-hand car market for affordability reasons.

You cannot have it both ways

Why shouldn’t the sale of used cars grow in the way that it has grown in the West, especially given that China’s average annual rural disposable income was apparently just $1,983 in 2017? This is an official number and so could well be an overestimation.

Equally, the environmental impact of selling more and more new vehicles has to be considered. The Chinese government has made what I believe is an unbreakable commitment to improve air quality.

Why should the government encourage more and more new vehicles on the road when there are plenty of second hand ones around? Second-hand sales were just 11% of sales in China last year. In the West they are typically 2-3 times new sales.

You can argue that the sale of new electric vehicles is the environmental solution. But even with heavy Chinese government subsidies it will be a long while before electric vehicles take over.

And by the time that does happen, China may have become the world leader in autonomous driving and ride hailing. Why own a car at all when it’s cheaper to call for a computer-driven ride on your Chinese-made very affordable smartphone?

Also, you simply cannot have it both ways. If you buy into the notion of China relentlessly moving towards Western middle-class income status then you simply must accept that environmental pressures will grow. This always happens as people get richer. There will also be pressure to spend less time in traffic jams.

China the eight cylinder engine of growth

Why then have we seen such stellar growth in auto sales since 2008? The reason is the exceptionally easy credit conditions of 2009-2017 which I believe are a thing of the permanent past. Sales on the levels we have seen since 2009 would have been impossible without very easy credit, as Chinese disposable and per capita income levels remain very low compared with the West.

Lower availability of lending in 2018 explains why overall new vehicle sales fell by 2.8% in 2018 compared with 2017. It also obviously explains why sales of new passenger cars were last year down by 4.1%. These were the first declines in decades as China reduced shadow lending by 73% – $684bn lower.

The problem for chemicals and auto companies is, as I said, false expectations about future autos growth in China. And take away Chinese growth from the last 13 years and remaining global sales would have been pretty pitiful.

The latest complete global autos data set I have available is for passenger car sales from January-November 2006 until January November 2018. The data show that sales in the major Western markets of the US, Europe and Japan were virtually unchanged at 34m during this period.

Excluding China, sales in the other six markets rose just 4.5% over the same period from 39.4m to 41.2m. Meanwhile, Chinese sales rose four-fold from 5.7m sales in 2006 to 22.1m to 2017 before falling in January-November 2018 – and during the full-year 2018.

It is not surprising, therefore, that General Motors, Volkswagen and BMW have generated a third to a half of their global profits from China. I wouldn’t be surprised if the pattern is the same amongst the chemicals companies that supply raw materials to the auto makers.

Implications for polypropylene

In my next blog, on Friday, I will detail the global impact on polypropylene (PP) of not only the slowdown in the Chinese auto market but also the overall economy (PP is heavily used in the autos sector). This will add global context to my post in late January, when I first flagged up how lower autos sales would impact Chinese PP demand.

Looking at just 2018-2020, my post on Friday will explain why global PP growth could be 6.5m tonnes lower than our base case. I will extend my downside forecasts out to as late as 2030.

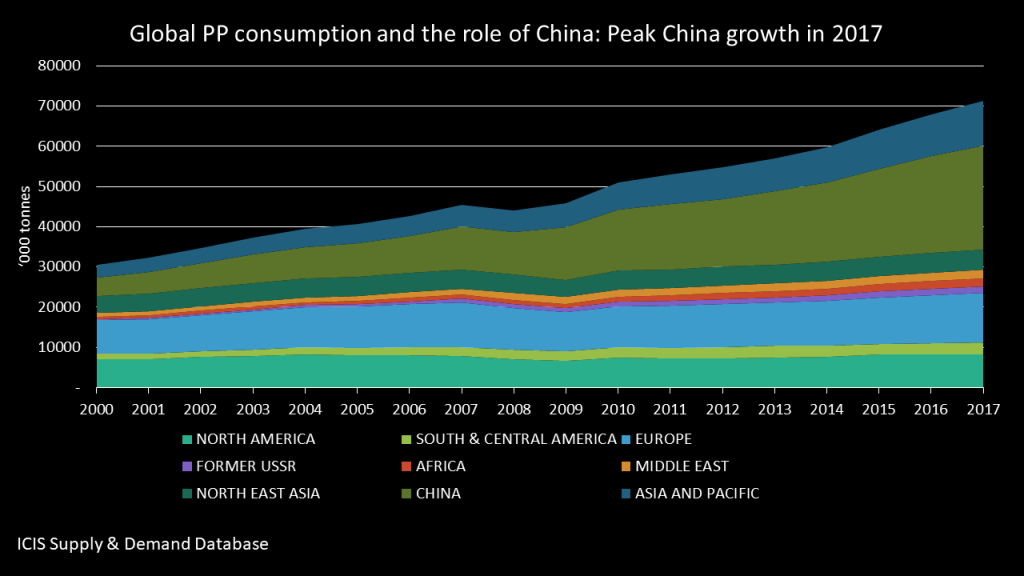

In the meantime, take a look at the chart at the beginning of this blog post. It shows how China’s PP consumption was just 4.6m tonnes in 2000 rising to 10.5m tonnes in 2008. During this period, China represented 20% of total global demand.

But then Chinese PP demand, as with autos and the rest of the economy, went into overdrive because of all that easy credit. Between 2009 and 2017 Chinese consumption grew from 13.1m tonnes to 25.9m tonnes. And crucially, as with the autos industry, China became much more important to global demand: In 2009-2017 its share of global consumption jumped to 33%.

As the heading on the chart says, China’s spectacular growth in PP demand has likely peaked, as is the case with autos.

“Come on, tell me something new. Of course China’s PP demand growth was always going to peak as its economy developed,” I can also here you saying.

Yes. Absolutely. But as my analysis shall show over the next few weeks it is the extent of the potential decline in Chinese PP growth that will be the issue.