By John Richardson

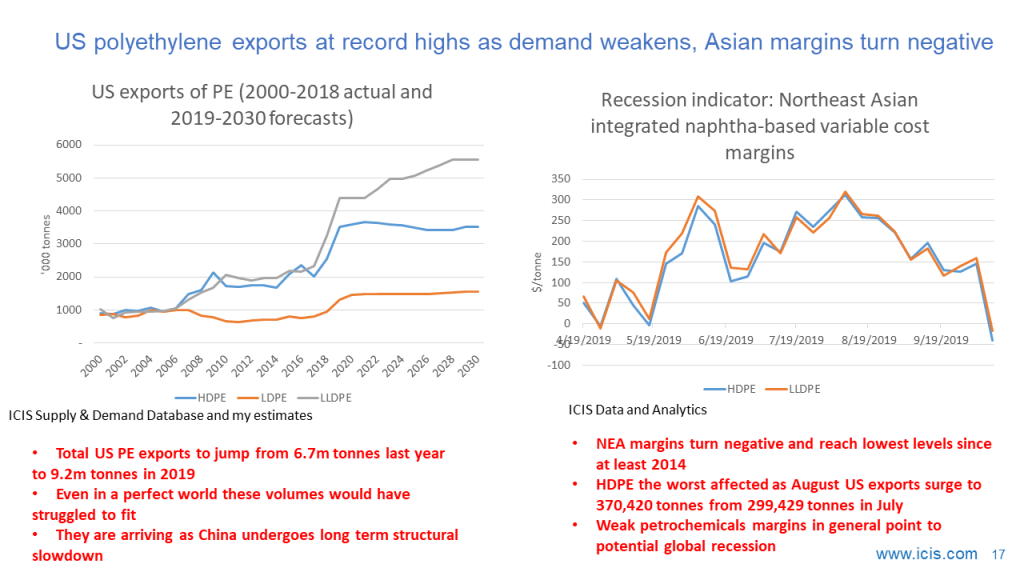

PERHAPS ONE could argue, but I certainly wouldn’t, that in a perfect world the extraordinary rise in US polyethylene (PE) exports, which are detailed in the chart on the left, would have just about found a comfortable home.

But when has the world ever been perfect? It certainly isn’t today: The IMF yesterday lowered its global growth forecast to just 3% for 2019, which would be the lowest level of growth since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. If this year’s growth were to reach 2.5%, this would constitute a recession, added the IMF.

The IMF cited rising tariffs, the result of the trade war, as a reason for trimming its growth forecast. But I believe a far bigger factor behind the global malaise are the structural changes in China, which still remain largely underreported and misunderstood.

To repeat, China rescued the global economy from the Global Financial Crisis as a result of the world’s biggest-ever economic stimulus. For reasons of debt and the environmental damage caused by excessive growth, stimulus has been withdrawn.

There is no going back. China will not, simply cannot, launch another wave of stimulus on the scale of 2009-2017, regardless of how bad the economic outlook becomes because of external factors including the trade war.

Sure, the trade war certainly isn’t helping. But, regardless of whether or not the trade war comes to an end (and in my view it won’t), we are moving into a world of permanently lower growth because of the changes taking place in China.

For the petrochemicals industry, this structural slowdown is an enormous deal. It is also a huge deal for the global economy:

- Focusing just on PE – and it is the same story in most of the other petrochemicals – in the ten years from 1999 until 2008, China’s PE consumption grew by 5.9m tonnes. But in the decade between 2009 and 2018, China’s demand jumped by 15.1m tonnes.

- In 1999-2008, the total value of China’s GDP grew from $1.1 trillion to $5.1 trillion. In 2009-2018 growth was again spectacular – from $6.1 trillion to $13.6 trillion.

Our base case forecast is that China’s PE demand will grow by 14.9m tonnes over the next ten years – 2019 until 2028. You need downside scenarios.

Yes, I get it. To some extent, China’s PE growth is divorced from changes in GDP because of the local-for-local nature of demand (less dependence on exports compared with other polymers), and the rise in packaging requirements for internet sales of daily necessities and cheap luxury goods.

But PE growth is not entirely divorced from the expansion of the overall economy. Of course not. Think of demand for collation stretch linear-low density polyethylene (LLDPE) film used to wrap consumer durables, such as washing machines, refrigerators and electronics. This is being affected by China’s slowdown. It is the same for high-density polyethylene (HDPE) petrol tanks now that we have gone beyond peak growth in China’s new-car sales.

Take just a few percentage points of our base case forecasts for Chinese PE demand in 2019-2028 and the global impact will be huge, given that since 2009 China has been the world’s biggest consumer of PE amongst all the other countries and regions. In 2018, China accounted for 23% of total global PE demand. Last year, this reached 33%.

Here is the other thing as well with PE: Drip, drip, little by little, or I suspect a lot quicker than most people anticipate, global demand is being eroded by the legislative and public pushback against the plastics rubbish crisis.

The here and now: Northeast Asian PE margins lowest since at least 2014.

That’s the big long term picture behind the implications of the rapid build-up in US PE exports in a market that cannot bear these volumes without major disruptions.

Let’s next focus on the here and now. Switch your attention to the chart on the right, showing our latest estimates of Northeast Asian (NEA) HDPE and LLDPE naphtha-based integrated variable cost margins. This is for the week ending 11 October.

In both cases, last week’s margins were negative and at their lowest levels since at least the beginning of 2014, when we began these margin assessments. In the case of LLDPE, this was the first time margins turned negative since we began our assessments.

Delve deeper into the details behind our numbers and you will find that co-product credits, from selling propylene, butadiene and aromatics etc., had remained pretty stable over the last 12 months. What had changed was a sharp decline in PE prices on the back of too much US supply.

The US has seen a sharp decline in its HDPE and LLDPE exports to China because of trade-war tariffs that total 30% on each polymer. US producers have adjusted to the loss of China market share by raising exports to Europe, Turkey, Malaysia, and most notably to Vietnam, where the US is now selling more HDPE and LLDPE than in China.

Producers in Saudi Arabia, Singapore and Malaysia etc. have been able to compensate for strong US competition in non-China destinations this by exporting more to China.

But these Saudi etc. exporters have more than just replaced missing US material in China; they have flooded China with PE.

China’s apparent demand growth in January-August 2019 on a year-on-year basis reached 13% compared with our estimate of actual growth for the full year of 7.7%. Apparent demand is net imports plus local production. Net imports were up by an average of 19% across the three PE grades with LLDPE net imports up by 23%.

This implies overstocking of 1.1m tonnes, based on our annual estimate of growth at 7.7%. I suspect, though, that excess inventories could be even higher than this as growth is unlikely to be as healthy as we have forecast.

Imports have quite clearly poured into China in the hope of major new economic stimulus. But that hasn’t happened (and, as I said, it will not happen). Lack of stimulus helps explain NEA margins swinging into negative territory. Another factor for the week ending 11 October was a rise in feedstock costs.

Meanwhile, US exports are surging. Total US HDPE exports look set to rise to 3.5m tonnes this year from 2.6m tonnes in 2018; LDPE shipments are line to reach 1.3m tonnes from 940,000 tonnes; and LLDPE exports are forecast to increase to 4.4m tonnes from 3.2m tonnes.

The heat from US HDPE imports has been particularly intense. In August, US HDPE exports increased to 370,420 tonnes from 299,429 tonnes in July, whereas LLDPE exports were more or less flat. US HDPE exports to Malaysia, Vietnam and Taiwan, Province of China, saw big month-on-month increases. This probably explains why NEA HDPE margins last week performed worse than those for LLDPE

Petrochemicals margins as a recession indicator

This is of course early days yet. One week of negative PE margins are hardly conclusive proof we are heading into a recession. But NEA and also Southeast Asian PE margins have been falling for many months now, as is the case with Asian ethylene glycols margins. Globally, also, chlor-alkali (caustic soda and chlorine) margins are sharply down.

The great thing about our petrochemicals margins data is that they serve as an early warning for manufacturers in just about every value chain, because, of course, petrochemicals are the raw materials for so many finished goods.

What is beyond doubt in my view, regardless of the timing of the inevitable next recession, is that we have arrived in a lower growth world because of the structural changes in China. A further negative factor specific to petrochemicals are the sustainability issues.