By John Richardson

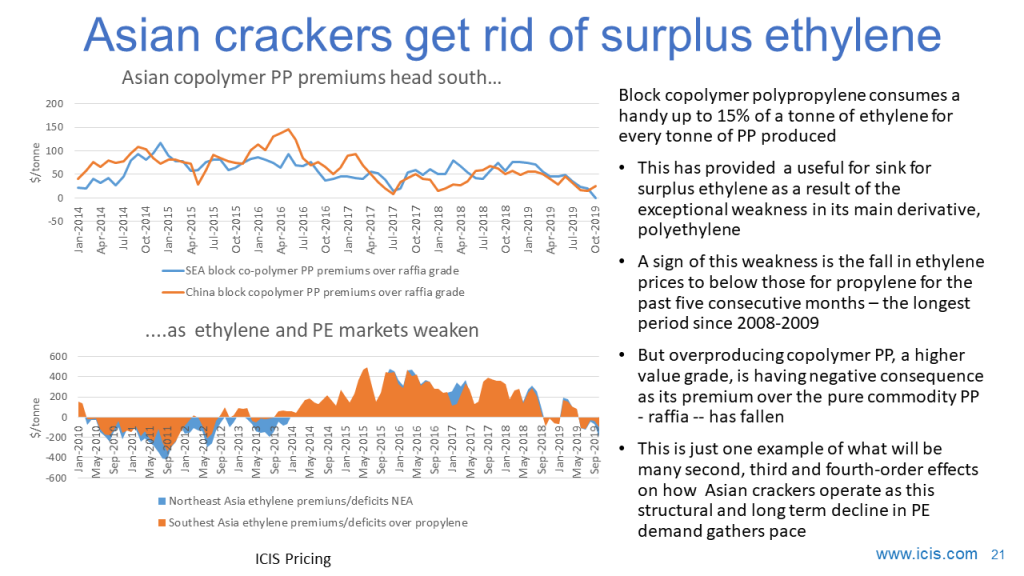

A SURE sign that the Asian ethylene-to-polyethylene (PE) markets are distressed comes from the above chart on the left which shows declines in block copolymer polypropylene (PP) premiums over homo-polymer raffia-grade PP since June of this year. In October in Southeast Asia (SEA), the price for the normally higher value block copolymer PP was lower than that for raffia grade.

Cracker-to-polyolefins producers have been getting rid of ethylene into copolymer PP that they would have otherwise used to make PE. Ethylene and PE margins are being squeezed by the vast oversupply resulting from the rise in US production during a time of weakening global demand.

It takes up to 15% of a tonne of ethylene to make a tonne of block copolymer PP. No ethylene is needed to produce raffia grade PP. Disposing of ethylene in this way underlines the point I made on Monday, which is that Asian cracker operators are not going to roll over and die. They will find ways of avoiding operating rate cutbacks, with the chance of any Asian cracker shutting down for market reasons pretty much close to zero.

Whilst block copolymer premiums over raffia nose-dived between June and October, random copolymer PP premiums over raffia grade have remained more or less unchanged. This is because random copolymer PP only consumes a maximum of 7% of ethylene per tonne of PP produced, and so obviously doesn’t get rid of as much undesired ethylene as block copolymer PP.

But watch this space. If ethylene-PE market conditions continue to deteriorate, we might seem also see overproduction of random copolymers.

A litmus test of the extent of the weakness in ethylene-PE markets will also be how long the dip in copolymer premiums lasts. As the chart again shows, so far there is nothing remarkable about the latest dip in premiums. It has happened several times before, most recently in 2017, and for longer periods. Premiums had also bounced back in November up until the 22nd of this month.

But any sustained recovery in premiums will likely encourage more block copolymer PP production as the Asian PE market is going to remain severely oversupplied for the next couple of years at least.

Battling through the downturn

The weakness in PE will continue to exert downward pressure on ethylene prices. SEA and NEA ethylene has been cheaper than propylene for the last five consecutive months – June until November, as the above chart on the right illustrates. This has contributed to attraction of getting rid of ethylene in block copolymer PP.

The last time that ethylene was cheaper than propylene for longer than five consecutive months was between May 2008 and November 2009. Then it was a case of tight propylene supply and booming derivatives demand. Now, as I said, the driver behind weak ethylene pricing is the difficulties in the PE market.

What other tactics might the Asian cracker operators employ as they battle hard through this downturn?

During the last downturn, “take or pay” naphtha purchasing contracts were said to be one of the reasons why no Asian cracker was idled. Naphtha was turned into olefins and then solidified into polymer pellets for which there was insufficient demand. The pellets were stacked first in warehouses and eventually in car parks, once the warehouses became full. This might happen again.

And as I said on Monday, no Asian cracker complex is an economic, social and political island. Parent companies may cross-subsidise petrochemicals operations, which has happened on several occasions in the past.Asian cracker operators will successfully apply for antidumping and safeguard duties against US PE cargoes. Governments will be in favour of duties because of the need to project local employment in a lower-growth world.

We are heading towards a much more regionalised petrochemicals business in general as priority is given to protecting local jobs and as geopolitical tensions build. Asia will become largely self-sufficient in petrochemicals as China draws the whole region into its giant new free trade and investment zone. In the EU, trade protectionism will take the form of environmental taxes on US and other PE imports.

Polyethylene is reaping what it has sown

As this latter point on EU environmental tariffs confirms, this is not a typical downturn which will be over in a couple of years. It is instead a major and permanent structural shift in the PE market.

Still not convinced? Then consider this announcement by Coca-Cola. By 2021, it will stop using any plastic shrink wrap (usually made from linear-low density PE) for any of its products in Europe. It will instead use cardboard. Coca-Cola claims that this will reduce its plastics consumption by 2,000 tonnes a year and its CO2 emissions by 3,000 tonnes a year.

In a report Coca-Cola produced for the Ellen MacArthur Foundation in March this year, the company said it produced 3m tonnes of plastic packaging a year. This includes not just PE, but also a huge volume of polyethylene terephthalate bottles.

Coca-Cola and many of the other major brand owners have made major commitments to ensure that all their packaging materials are eventually compostable, biodegradable or recyclable. For some PE applications this will be technically and economically impossible. Expect brand owner commitments to result in the loss of many million tonnes of PE demand.

Concerns are being expressed that all this focus on plastic rubbish has drawn attention away from the much bigger problem of climate change. True to some extent. But as the Coca-Cola announcement demonstrates, loss of polymer demand will be the result of analysis linking plastic rubbish with CO2 emissions.

The big brand owners cannot afford to lose sight of climate change, and, as we all know, petrochemical plants generate a lot of greenhouse gases, as does upstream oil and gas production. Also, the economic rationale of this industry has built on building plants a long way from end-use markets. This generates even more CO2 through transporting polymer cargoes say from the US to Asia.

Are total petrochemicals emissions, from oil and gas extraction through to final delivery, any worse than manufacturing other packaging materials such as paper? This will not always be the case. But sorting accurate from inaccurate science will be very difficult in an environment where emotion dominates. Emotions are against us because of the public anger over plastic pollution. This anger, is to a large extent, our fault because we have spent decades ignoring the highly visible problem of plastic rubbish in the environment. You reap what you sow.

Conclusion: Asia for Asia’s sake

The environmental issues might seem a million miles away from down-to-earth and short term business decisions such as disposing of unwanted ethylene in co-polymer PP production.

But there is a vital connection here. The more PE demand is lost the more agile cracker operators will need to be in order to sustain profitability. And it is not just in PE where we are seeing major structural changes in demand. Polypropylene (PP) markets are undergoing major long term changes, which I have discussed before and will discuss again in later posts. As PP demand growth continues to weaken, getting rid of surplus ethylene in the copolymer market will obviously become less viable.

I must stress again, though, that the Asian naphtha cracker industry will muddle through, thanks to a combination of flexible derivatives production and parent company and government support. I actually see some of the new investments in the US as more vulnerable.

Asian cracker operators will also over the long term benefit from being in the right location as China builds the world’s biggest-ever free-trade zone. Asia will very much serve Asia as the region moves towards self-sufficiency in petrochemicals. This is yet another reason why no Asian cracker should or will shut down for market reasons. More new crackers will instead be built in Asia, especially in China.