By John Richardson

IT IS a fantastic achievement. “Over the last 25 years, more than a billion people have lifted themselves out of extreme poverty, and the global poverty rate is now lower than it has ever been in recorded history. This is one of the greatest human achievements of our time,” said World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim in September 2018. Extreme poverty is defined by the World Bank as living on less than $1.90 a day.

But much of this great work is now in jeopardy because of the coronavirus pandemic. The developing and emerging economies “have been buffeted, to varying degrees, by a global slump, sharp falls in commodity prices, flight from risk in financial markets, a huge decline in remittances and receipts from tourism and a large decline in world trade,” wrote Martin Wolf in The Financial Times.

Second- and third-order effects also need to be considered. The crisis threatens to reduce funding of already badly funded welfare and healthcare systems. Shortages of food may make millions more vulnerable to diseases other than the coronavirus. Education, so crucial for escaping poverty, could be permanently damaged.

Martin Wolf quotes a recent high-level plea to the G20 – involving an article co-authored by former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown – which warned of 420m additional people being pushed into extreme poverty.

“The World Food Programme has estimated that 26m of our fellow citizens are likely to suffer from crisis levels of hunger – an increase of 130m over pre-pandemic levels,” wrote the authors of the plea.

As the number of coronavirus cases continues to climb in developing and emerging countries, lockdowns are nevertheless still being eased. Governments have no choice because of the many millions of “day-rate labourers” who were unable to feed themselves when lockdowns were at their height.

The emergence from poverty is a major driver of petrochemicals growth, e.g. a day-rate labourer in India scraping enough money together to buy a motor scooter or, at a much more modest level, a whole bottle of shampoo rather than just single-serve sachet of shampoo.

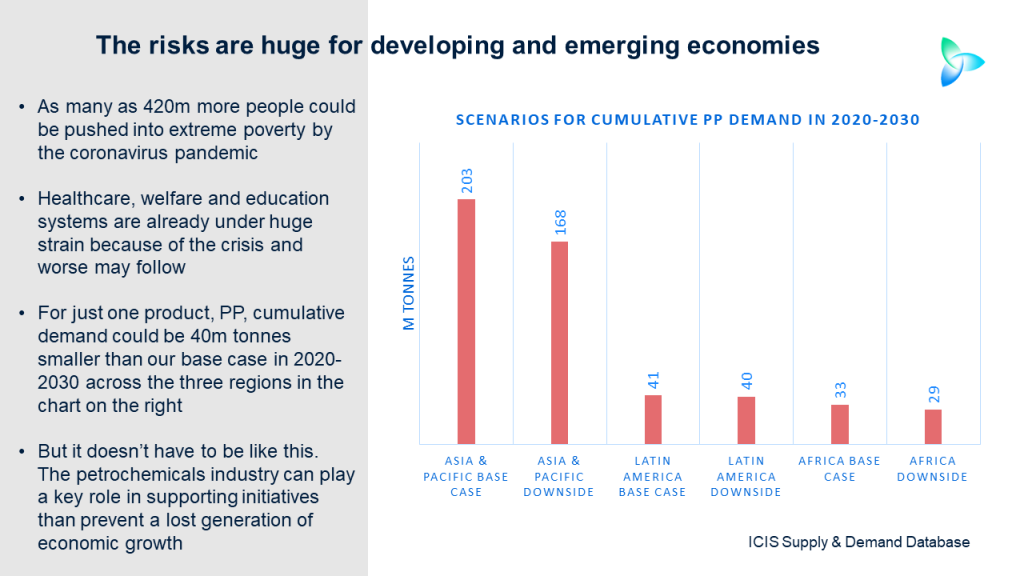

Let’s think about what this could mean for growth in one polymer – polypropylene (PP) – by making use of the ICIS Supply & Demand Database:

- Our base case for the Asia & Pacific region sees 2020-2030 demand growth averaging 7% per annum. Cut growth during each year by half and cumulative consumption is 35.4m tonnes lower.

- Repeat the same exercise for Africa, where our base case sees average annual growth at 5%, and demand is 4.4m tonnes smaller.

- As for Latin America, we expect average 2020-2030 annual average growth at 4%. Once again, reduce this by half and the region’s cumulative demand falls by 825,000 tonnes.

- This comes to a total loss of around 40m tonnes of demand versus our base case.

This is the dollar-and-cents reason why petrochemical companies can be part of the solution to the crisis confronting developing and emerging economies. It is, of course, also the right thing to do.

So, how can our industry help? Lobby politicians to adopt the recommendations made by Gordon Brown, Helen Clark – the former New Zealand PM – and the other authors of the article to the G20.

The recommendations included global coordination of the development, mass manufacture and equitable distribution of a vaccine or vaccines to ensure that they are universally and freely available as quickly as possible.

Every G20 member should support in full the $7.4bn replenishment of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, which between 2021 and 2025 will immunise 300m children, saving up to 8m lives. While we fight the coronavirus we must not allow the resurgence of other infectious diseases, added the authors.

Closer cross-border collaboration is essential to increase now – and for the future – the limited global supply of vital medical equipment and to make testing accessible in every country, they wrote

Developing countries need immediate support from the World Health Organization and others to build up their health systems and capacities, as well as to improve their social safety nets, they argued.

They also recommended that G20 countries should support the UN’s appeal for support for refugees, displaced persons and others who rely on humanitarian aid.

Individual petrochemical companies are also no doubt already involved in their own relief efforts, if the tremendous efforts they have made in helping to step up production of personal protective equipment is anything to go by.

More broadly across all industry sectors and governments, what is required are levels of cooperation that seem unlikely given the rise of nationalist politics and anti-globalisation. What if we fail to achieve these levels of cooperation? This is something I prefer not to think about.