By John Richardson

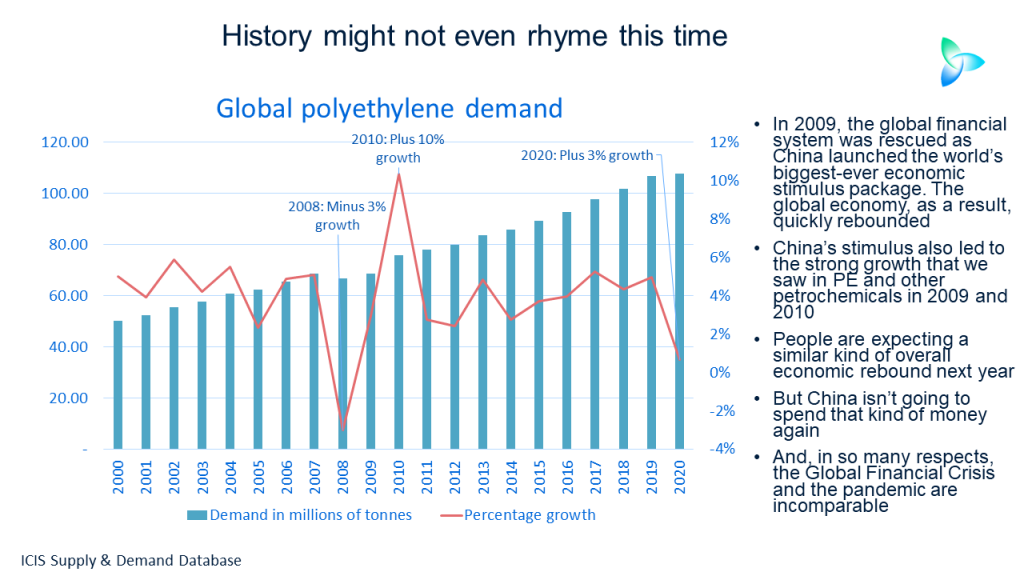

WE were very lucky in 2010, as the above chart illustrates. Global demand for polyethylene (PE), which had fallen to minus 3% in 2008 because of the Global Financial Crisis, bounced back to 10% growth. We were lucky for two reasons.

Firstly, the world’s financial system was rescued, which at one stage at the height of the crisis looked as if it might collapse. The rescue relieved the pressure on credit that had caused a sharp decline in global trade in Q4 2008 and a collapse in oil and other commodity prices. Financing was available again – and at historically low costs as monetary stimulus kicked in. Global trade rebounded as did commodity prices.

The second reason, which is still not widely understood, was China. Its economic stimulus programme, the biggest in history, led to very strong rebounds in global and Chinese growth. In the case of PE, Chinese demand growth fell to 1% in 2008 from 8% the previous year. But in 2009, local demand expanded by an extraordinary 31%. This then helped ensure that global growth reached 10% in 2010.

The unprecedented injection of money into the Chinese economy boosted global manufacturing demand in general and created a great deal of local wealth for those who invested in real estate or other frothy assets. And more broadly, Chinese stimulus, by making local people richer, reduced China’s dependence on exports as a source of growth. China’s exports contributed just 18% to the country’s total GDP last year, down from more than a third a decade ago, thanks mainly to a rise in local incomes.

Apologies to those of you who know all of this. But I felt that recounting history was essential because some people continue to believe that history of the Global Financial Crisis is about to repeat itself. They believe we will see a strong V-shaped recovery in 2021, just as we did in 2009-2010. On this occasion, history might not even rhyme, never mind repeat itself.

These two events are virtually incomparable. This is of course a health crisis and not a financial crisis. Because it is a health crisis, it cannot be resolved by Ben Bernanke, a few other people at the US Fed, Western politicians and China’s central bank. Today’s health crisis is immensely more complicated and more widespread than the events of 2008.

The only solution to the pandemic, in my view, is an effective vaccine, and, as I discussed on Monday, an effective vaccine is years away, assuming we get one at all. Proving the efficacy and safety of any vaccine is just one of the many challenges. There are also the challenges of producing and distributing the vaccine globally, and of ensuring that enough people receive the drug to achieve herd immunity.

On to China. Its new focus, because of what I believe is a permanent split with the US and perhaps also some other Western countries, is “domestic circulation”, which will be the cornerstone of its 14th Five-Year-Plan (2021-2025). I will discuss in detail what this means for the global petrochemicals industry in my post on Monday.

Domestic circulation involves China become much more self-reliant. It will reduce petrochemicals, high-tech components and consumer-goods imports in favour of domestic production as a hedge against a hostile geopolitical environment. China will not come to the rescue of the petrochemicals industry and global economy in the way that it did in 2009 through a broad-based and indiscriminate surge in its imports.

Further, there is the debt issue that will limit a surge in Chinese imports. China’s huge stimulus package led to a harmful rise in speculative financing, via its shadow-banking system, over-frothy real estate sector and a lot of bad debts. The shadow banking sector has been brought under control with the local bond market replacing more risky forms of financing.

China won’t therefore go backwards with another stimulus programme on the scale of 2009. The data show that its latest stimulus programme – which is based primarily on boosting local online sales and on better infrastructure, especially in China’s poorer western provinces – is worth 5% of the country’s GDP, less than half the size of US stimulus.

2021 outlook for petrochemicals

There will, in my view, be no big recovery in the global economy because an effective vaccine is some distance away – and because political and social issues will get in the way of any other solutions.

Demand for food packaging and hygiene products in developed markets – and the durable goods that people in greater volumes as they spend more time at home (home appliances, computers and office furniture etc.) – may continue to outperform the global economy.

Or demand for food packaging and computers might instead decline. The outcome will largely depend on the extent and effectiveness of future government stimulus that has raised the incomes of low-paid workers. This is of course critical for PE and for other polymers that go into packaging, such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polypropylene (PP) and polystyrene (PS).

A lot will also hinge on the growing impact of the long-term decline in tourism on packaging demand. Every extra PET water bottle consumed in the UK is one less bottle consumed in Spain or Greece.

We also need to evaluate the loss of packaging demand at airports and even onboard flights, not inconsiderable when you consider the amount we used to fly before the pandemic. Next think of all the cafes, the restaurants and the bars that will soon have to shut down because we are not going to be returning to our offices anytime soon.

But because of the rise of extreme poverty, it could be that demand for food packaging, personal care and hygiene products has declined in the developing world. When you find yourself suddenly forced to live on less than $1.90 a day, buying a bottle of shampoo can be beyond your means.

The effect on the developing world is only going to get worse, I am afraid. This article in The Wall Street Journal helps explain why; some 80% of programmes for fighting HIV, tuberculosis and malaria—which together kill millions each year—have been disrupted due to the pandemic; shortage of medical staff and underfunded healthcare systems are preventing coronavirus patients from getting the care that they need; extended lockdowns are inflicting even more damage on already fragile economies.

Think, also, of the collapse in remittance payments to the developing world because of developed-world lockdowns and the inability of children in poorer countries to attend school and so get the education they need to escape poverty.

As for the petrochemical that go into manufacturing cars, aeroplanes, buses and some sectors of construction including commercial property, I cannot see any kind of recovery after a very bad 2020. Will garment sales recover? I doubt it given the losses of income and the amount of clothing left in inventories.

There is a way forward for the petrochemicals industry as I have been discussing since the pandemic began. This involves focusing on value rather than volumes (including societal and environmental value), localisation of supply chains, sustainability and affordability. We can ill afford to be distracted from this focus by what I see as unrealistic expectations of a swift return to pre-pandemic market conditions.