By John Richardson

A NEW RESEARCH PAPER by economists Kenneth Rogoff and Yuanchen Yang underlines the scale of what is at stake for petrochemicals demand if China doesn’t blink and sticks to its deleveraging of the real estate sector.

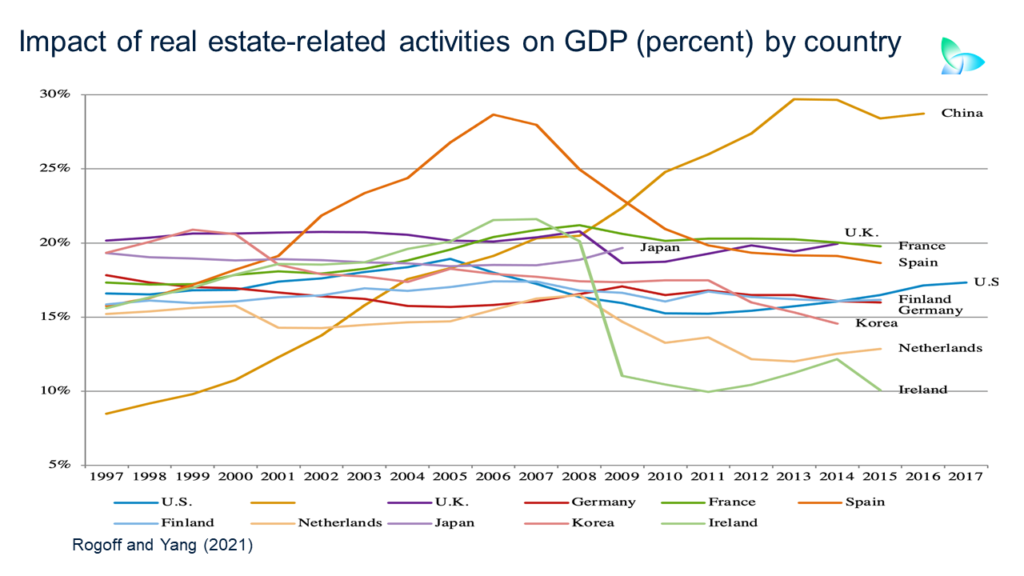

The authors found that 29% of the Chinese economy is dependent on the property sector when you consider both construction activity and related services. The extent of China’s dependence on real estate is a historic first. Only Spain came close to being as exposed as China is today in 2006, as the chart below shows.

The study added that China had one of the world’s highest housing vacancy rates, at more than 20%.

More than 90% urban households already owned their home, the authors said.

Their research found that during 2018, the latest year where data is available, 87% of new home sales went to buyers who already owned a dwelling. It would take around two years for all China’s unsold housing to be sold at current sale rates, they concluded.

And here, quoting a Financial Times review of the paper are, in my view, their most important findings:

“On Rogoff and Yang’s numbers, real estate’s share of GDP increased by almost 10 percentage points (or about half the starting share) in the five years following the global financial crisis, and then stayed flat near 30.

“On a rough approximation, that means these activities contributed nearly half of China’s strong GDP growth in those years, and a continuing near-30% or so of growth in the ensuing years.”

This underlines my argument that without China’s giant late 2008 economic stimulus package, the country’s petrochemicals demand growth would have been a lot weaker than was the case with major negative knock-on consequences for the rest of the world. Much of the stimulus ended up fuelling the property bubble.

No signs that China is going to blink

If China were to blink and relax lending conditions for real estate, the dangerous economic distortions detailed by Rogoff and Yang would only get worse.

Right now, there are no signs of Beijing relenting. As one senior polyolefins industry source said, “They are prepared to take the pain now”.

Close and extensive reading of China’s state-run media has always been hugely useful in assessing the political and economic mood. This Xinhua article is instructive.

“Financial institutions should cooperate with related authorities to maintain the steady and healthy development of China’s property market,” wrote Xinhua in its report on a joint meeting last week between the People’s Bank of China and the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission.

“Under the principle that ‘houses are for living in, not for speculation’ [President Xi Jinping’s principle], these institutions should implement prudential management for real estate finance,” the wire service added.

“Housing should never be used as a short-term stimulus for economic growth, the meeting said, calling for efforts to continue improving the financial policy for housing rental,” Xinhua reported.

How painful will the rebalancing be? Quite obviously extremely painful as real estate accounts for an extraordinary 29% of China’s GDP.

Think about not just the lost construction activity, but also all the conspicuous consumption over the last 13 years connected with the property bubble.

Luxury car, clothing and wine sales would have been nowhere as strong as they were without the bubble. There is a risk that these sales will be nowhere as strong in the future.

And remember that linked to the real estate crackdown are belated efforts to hit CO2 emissions reduction targets set under the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025).

The attempts to cut back on CO2 emissions have contributed to energy shortages that threaten China’s ability to fulfil export orders during this year’s peak manufacturing season, which, as always, runs from August until October.

During the season, China’s export-focused factories ramp up output to meet orders from the West in time for Christmas.

China is attempting to secure more imported liquified natural gas to keep the factories running and provide heating for homes during the winter, said the Financial Times.

But more than 60% of Chinese power generation is via coal, which produces more CO2 emissions in power plants than natural gas.

This indicates that if Beijing continues to pressure the provinces to hit their emissions reduction targets, continued loss of substantial amounts of industrial production is inevitable.

As the emission cuts are, as I said, intimately tied into the crackdown on the property sector, it seems very possible that the central government will keep the pressure on the provinces to meet their CO2 targets.

Short-term implications for polyethylene demand

As the Rogoff and Yang research indicates, the long-term implications for Chinese petrochemicals demand growth are huge, huge, huge – because real estate has played such a big role in driving the country’s GDP growth since 2008. I will revisit this subject in later posts.

Here, I will focus just on the short-term implications for polyethylene (PE). The chart below summarises our latest demand data (China customs net import data plus our estimates of local production).

Usually, Q4 sees strong demand because of the peak manufacturing season – and because of the Golden Week Holiday and the Singles’ Day sales promotion event. This year, Golden Week takes place on 1-7 October with Singles’ Day on 11 November.

But for the reasons detailed above, this year’s fourth quarter could turn out to be disappointing.

Our latest data show that China’s total PE demand in 2021 is set to be 1.6m lower than in 2020, if the January-July 2021 trends were to continue for the rest of this year. This year’s demand, though, would still be 1.9m tonnes higher than in 2019.

Because I see the property deleveraging and CO2 emissions reduction programmes continuing, I believe there is a risk that the final demand numbers for 2021 will be worse than is assumed above.

The same applies to my latest estimates for 2021 PE imports. The chart below is based on assuming that the import trends (as opposed to the net import trends) that we saw in January-August 2021 continue for the rest of the year.

If the January-August trends were to continue, total PE imports would be 3.4m tonnes lower than in 2020 and 1.4m tonnes lower than in 2019.

There is some optimism out there that Chinese imports will improve in Q4 because of the cutbacks in coal-based output resulting from the emissions-reduction targets – and because power shortages will cause lower PE production in general.

I am not convinced. Because the demand outlook looks bleak, we might see no pick up at all in imports. Perhaps imports for the full-year 2021 will even be weaker than is suggested in the chart above.

Conclusion: this really is a paradigm shift

“Paradigm shift” is a very much overused phrase as it is attention grabbing. But on this occasion, I see it as right to talk about paradigm shifts in China.

China is, as I’ve discussed before, attempting to build an entirely new growth model. In the long term I believe China will be successful, but the short-term risks are very significant.

Therefore, please do not assume that the rest of this year and 2022 will be “business as usual”. There is little evidence to suggest this will be the case.