By John Richardson

Executive Summary

CHINA’S POWER shortages could fixed by the end of this month or early November, I was told by a senior polyolefins industry source. Three other contacts concurred.

My contacts could be wrong, of course. A coal trader quoted by Reuters said that the energy shortages could continue throughout the fourth quarter and possibly into early 2021.

Extensive flooding in Shanxi province over the weekend, where dozens of coal mines are located, supports the case that the energy shortages could drag on.

The energy shortages are not just the result of China’s emissions-reduction programme, which seems likely to continue for the long-term because this is a key element of China’s “common prosperity” policy pivot.

Other factors behind the shortages include reduced coal supplies from Russia and Indonesia and the investment and export-driven nature of China’s recovery from the pandemic.

This means China has several policy levers it can pull to relieve the shortages. Evidence suggests it is pulling the levers very hard.

When the energy shortages end, what will be left exposed is weaker petrochemicals demand resulting from another key component of “common prosperity – deleveraging the real-estate sector.

When power supplies return to normal, be prepared for tightness in petrochemicals markets to disappear and for downward pressure on markets to resume.

In this post, I examine today’s tightness in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and the effect on their margins.

PVC has been more affected by the coal shortages than HDPE, masking in the case of PVC what both polymers share: much weaker demand in 2021 than had been expected.

The demand weakness will likely continue because of the “common prosperity” reforms, which involve a complete remaking of China’s economic growth model.

The old investment-led growth model appears to have run out of road, leaving Beijing with no options other than pressing ahead with the reforms.

China’s big push to tackle its energy crisis

China is doing everything it can to bring the energy crisis to end. When the government wants to get something done it quite often gets it done in pretty quick time.

My sources confirmed reports in the Financial Times, the Wall Street Journal and on Bloomberg that the government is pulling out all the stops to fix the problem that is affecting most of China’s provinces, according to the ICIS map below.

“Chinese state media quoted Premier Li Keqiang as saying the country will secure its energy and power supplies following a series of blackouts and shortages,” said the FT.

Bloomberg wrote that central government officials had ordered state-owned energy companies to secure supplies for this winter at all costs. The instruction had come directly from Han Zheng, the vice-premier who oversees the country’s energy sector, the wire service said.

Other media reports said that local coal producers had pledged to accelerate output to compensate for rail and port logistics problems that had hampered coal imports from Russia and floods in Indonesia that had reduced the country’s shipments to China.

One million tonnes of Australian coal, which had been held in China’s coastal bonded warehouses for months because of a geopolitical dispute with Australia, would be released into the local market, said Reuters.

China is also apparently considering importing more coal from Australia and other countries.

Solving the coal supply issue is crucial as it still accounts for some 60% of China’s electricity generation despite big growth in renewables and natural gas generation capacity. The latter’s power plants are mainly supplied by imported liquefied natural gas (LNG).

On the theme of LNG, China appears to be buying extra cargoes, one of the reasons why international prices are going through the roof.

“The core point here is that China has lots of options, lots of policy levers to relieve the power shortages, because there are many causes, and therefore many potential solutions, for the crisis,” said one of my contacts.

Another lever is relaxing the electricity price caps that have led some power generators to cut back on output, as the generators have been unable to pass on surging coal costs. Domestic coal prices rose by around 80% between June and December.

But the Chinese government cannot, of course, do anything about the weather.

“Lower-than-usual supply of renewable energy has exacerbated the power supply issue in some provinces, wrote the Wall Street Journal.

The southwestern province of Yunnan, which produces hydropower, had been struggling with droughts throughout the year, with wind farms in north-eastern China more recently hit by a lack of wind, the newspaper said.

And now energy markets are having to contend with the weekend floods in Shanxi province which have displaced nearly two million people, forcing the closure of dozens of mines. Coal futures traded on the Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange reached an all-time on Monday, said the FT.

At some point over the next few months, however, reduced factory output is expected to help clear the skies for the Beijing Winter Olympics. The Olympics take place between 4 and 20 February 2022. Reduced manufacturing would, of course, lower energy demand.

But hey, “It’s demand, stupid”

A slowing economy will also, I believe, eventually play a role in fixing the energy crisis. To paraphrase James Carville, “It’s demand, stupid”.

Carville, who was a strategist on Bill Clinton’s successful 1999 presidential campaign, actually said, “It’s the economy, stupid”, as he got campaign workers to focus on a recession that had occurred under the incumbent president, George HW Bush.

As with the economy and this successful presidential campaign, success in analysing China over the next six to 18 months depends more on demand than supply factors.

A lack of sufficient focus on demand is leading some people to believe that yet another reason for the electricity shortages – Beijing’s emissions-reduction programme – guarantees tight electricity supply and tight Asian petrochemicals markets over the next few months.

The emissions reduction programme looks set to continue into next year as China is said to be a long way behind President Xi Jinping’s revised target, announced last September, of reaching peak emissions before 2030. The earlier target was peak emissions by 2030.

The programme is at the very core of China’s “common prosperity” pivot, the biggest shift in government policy since at least 2009 – and the biggest event in the global economy since at least that year.

A symptom of life-threatening pollution is CO2 emissions. Another core part of “common prosperity” is improving the quality of life in China, through making further progress in cleaning up the air, water and soil.

And China is a long way behind the eight-ball if it is going to hit its various emissions-reduction targets, according to this excellent analysis from Carbon Brief.

If CO2 emissions kept increasing at their Q1 2021 rate until the end of this year, they would be up by approximately 9% over the pre-pandemic year of 2019, said Carbon Brief.

This would leave virtually no space for further emissions growth in 2022-2025 if China were to hit its 14th Five-Year-Plan target for reducing emissions, said Carbon Brief. The 14th Five-Year-Plan runs from 2021 until 2025.

The cause of the emissions surge is the investment and export-intensive nature of China’s recovery from the pandemic – another reason for coal shortages. Up until August this year, monthly year-on-year coal demand in 2021 had increased by around 20%.

As I said, therefore, the emissions control policy will continue along with a significant economic slowdown as China builds its new growth model, as reducing CO2 output, property deleveraging – and also reducing income inequality – are all part of the same policy platform.

Do not underestimate how significant real-estate deleveraging will be for Chinese petrochemicals demand. A study by Harvard University’s Kenneth Rogoff and Yuanchen Yang found that:

- 29% of the Chinese economy is dependent on the property sector when you consider both construction activity and related services.

- The extent of China’s dependence on real estate is a historic first. Only Spain came close in 2006 to being as dependent as China is today

- Real estate’s share of GDP increased by almost 10 percentage points (or about half the starting share) in the five years following the Global Financial Crisis, and then stayed flat near 30.

- On a rough approximation, that means these activities contributed nearly half of China’s strong GDP growth in those years, and a continuing near-30% or so of growth in the ensuing years,

A sign of the pain to come was a report by Reuters of a 17.5% year-on-year fall in Chinese land sales in August this year. This could have major implications for local government revenues, as the bulk of their revenues come from land sales.

“Land sales soared to a record 8.4tr yuan ($1.3tr) in 2020, the equivalent of Australia’s annual gross domestic product, bolstering fiscal budgets in a pandemic year,” said Reuters.

What this means for PVC and HDPE markets

I will now focus on what this means for two polymers – PVC and HDPE. Let us start with the chart below, from our suite of ICIS margin assessments.

As you can see, all three Asian assessments have recently been at record highs on higher PVC pricing.

Take, as an example, China’s carbide-based margins that jumped by 19% during the week ended 1 October following an 8% rise in prices. Margins across all three assessments in September-October rose to above $1,000/tonne for the first time since we began our assessments in January 2014.

This makes sense from a supply perspective as 80% of China’s vinyl chloride (VCM) production, and therefore, PVC production is via the carbide route. All VCM is used to make PVC.

The carbide route starts with calcium carbonate reacted with coke in electric arc furnaces to produce calcium carbide. The calcium carbide is then reacted to make acetylene and acetylene is combined with chlorine to make VCM, which is then polymerised to make PVC.

The shortages of coal have limited calcium carbide production, with the shortages of electricity limiting output from chlor-alkali plant that make chlorine and its co-product, caustic soda.

In contract with PVC, HDPE margins in Asia fell to close to zero during the week ended 24 September, the lowest level since turning negative in late 2019 and early 2020. They recovered slightly during the week ended 1 October but remained historically very low (see the chart below).

One explanation for the difference is that only around 30% of China’s HDPE production is via coal and then the methanol-to-olefins process. This is compared with, as I said, 80% of Chinese PVC made from coal.

A second factor is the big differences in 2021 capacity growth. ICIS forecasts that Chinese PVC capacity will rise by only 3% in 2021 over 2020, whereas HDPE capacity will increase by 25%.

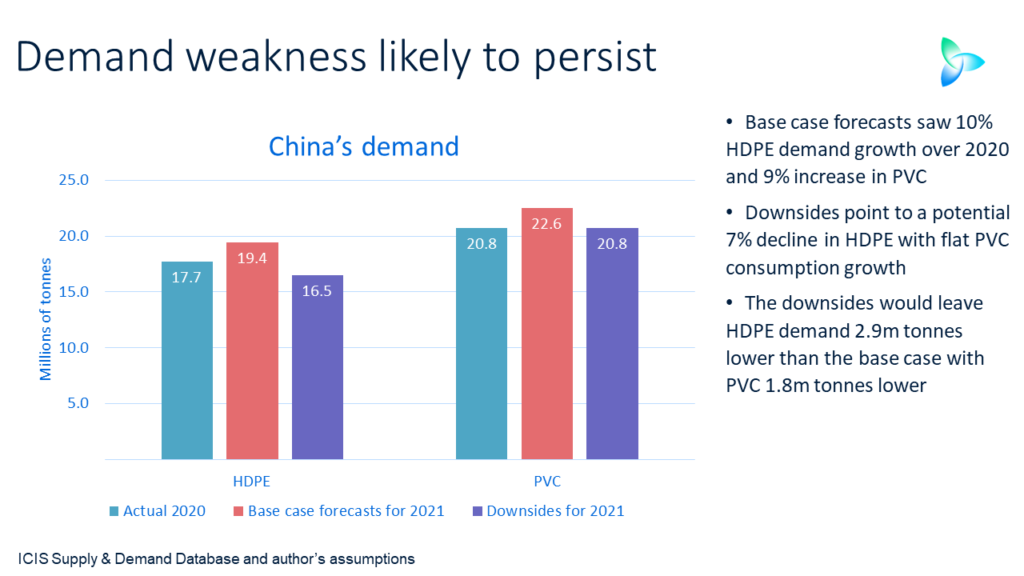

But remember, also, that this was supposed to be another banner year for Chinese petrochemicals demand following strong growth in 2020. It hasn’t turned out to be like this as the chart below illustrates. Expect more of the same next year.

What I believe happened from January until August this year was slower-than-expected consumption growth on a pullback in government infrastructure spending. There was also a slowdown in exports of manufactured goods by volume because of container freight and semiconductor shortages.

A major factor behind my estimate of weaker-than-expected PVC growth is a surge in China’s exports, which were up by 231% year on year in January-August 2021 to 1.4m tonnes. This led to a big fall in net imports.

The surge in exports was down to better overseas netbacks and weak demand in China, I’ve been told.

Conclusion: demand to overtake energy supply issues

China’s demand will become the dominant factor driving global HDPE and PVC markets over the next 6-18 months. In 2020, China accounted for 36% of global HDPE and 44% of global PVC consumption, way ahead of any other region.

Beijing might blink, as I’ve discussed before, by relaxing controls on real estate – along with perhaps other economic stimulus measures. But I see this is as unlikely because the old investment-led economic growth model no longer works.

You need to build a scenario for the next 6-18 months that factors in lower Chinese growth than consensus thinking suggests. You then need to stress test your business model under this scenario.