By John Richardson

AGAIN, DON’T say I didn’t tell you. In my 11 October blog post, having talked to people who know what they are talking about, I flagged up the possibility that China’s energy shortages could be fixed a lot quicker than many people were suggesting.

Those in the know about China told me that Beijing had multiple policy levers it could pull to fix the energy shortages, which centred on a lack of coal as some 60% of Chinese electricity is generated by coal. They said that the crisis could be pretty much over by the end of October, despite the conventional view that it would drag on until early 2021.

Bloomberg reported that China’s electricity output climbed by 11.1% in October on a year-on-year basis. This growth is remarkable when you consider that in October last year, China was in the middle of an exceptionally strong export-driven recovery from the pandemic. This recovery obviously required lots of electricity.

China’s coal prices jumped to an average $270/tonne in October this year from $150/tonne in May 2021. Over the last three weeks they have fallen back to $150/tonne. Reuters said that China’s coal output in October was the highest since March 2015.

On a year-on-year basis in January-October, China’s coal output was 4% higher, added Reuters, quoting data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

“Since July [2021], China has approved expansions at more than 153 coal mines, which could add 55m tonnes of coal output in the fourth quarter, the National Development and Reform Commission said last month,” the wire service added.

The expansions sanctioned since July obviously predated the September-October panic about energy shortages. So, why the shortages then?

“In any heavily centrally planned economy, instructions from the centre to local governments can either be miscalculated or misinterpreted, and I think that’s what happened in September and October at the height of the energy crisis,” said a polyolefins industry source.

“China was never structurally short of coal. It was just that a few policy issues, along with reduced import availability, led to some temporary shortages. Now they appear to have been largely fixed.”

His comments were backed up by an article in the South China Morning Post. The newspaper wrote:

“China does not have a shortage of coal, and the nationwide power cuts were a ‘man-made crisis’ and a ‘big mistake’, according to domestic coal industry insiders who blame Beijing for its miscalculations,” wrote the newspaper.

Key to increasing supply in October was not only higher output at mines, but also a change in the electricity pricing system that had prevented generators from passing on soaring costs. Lack of pricing flexibility had led to reduced power output.

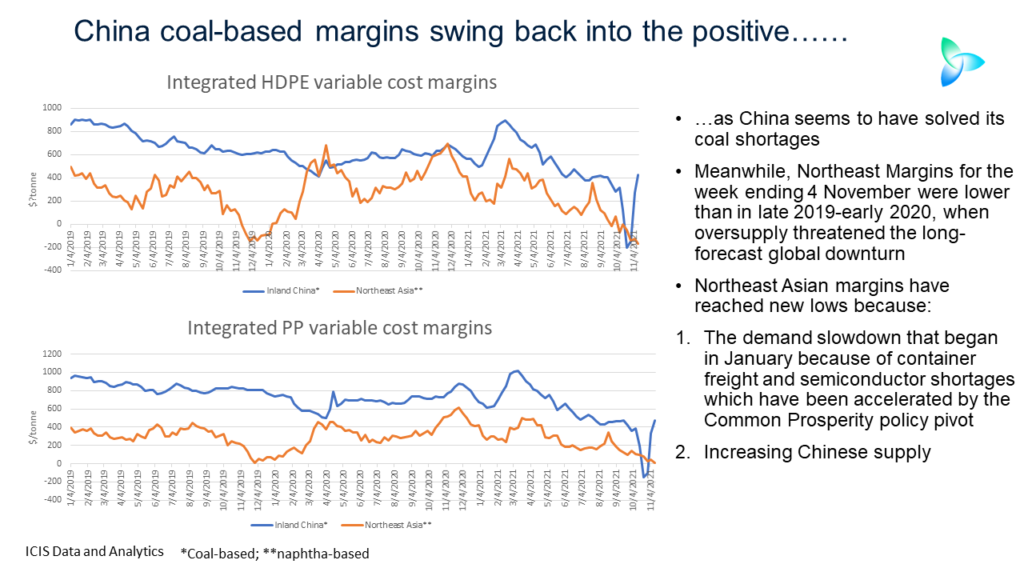

What further points towards receding coal shortages is the slide below, showing integrated variable cost high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and polypropylene (PP) margins in inland China and in northeast Asia (NEA), which includes coastal China as well as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

As you can see, coal-based inland China margins are back into positive territory and now exceed those for naphtha-based margins in NEA.

So much for the theory of improving Chinese polyolefins imports in Q4 this year on the back of cutbacks at coal-based plants resulting from expensive coal and shortages of coal. Some 30% of China’s PP production and 15% of HDPE output are coal-based.

In my view, even if the coal shortages had continued, a Q4 increase in imports was unlikely to happen because of declining PE and PP demand growth and rising Chinese self-sufficiency (more on these themes later in the post).

Clearly, with the coal shortages seemingly pretty much over, there is even less of a chance of a rise in imports.

What government policies are telling us about China’s polyolefins demand and self-sufficiency

You will also notice in the above chart that NEA margins during the week ending 4 November 2021 were lower than in late 2019-early 2020.

The earlier period marked the point when the long-awaited global downturn appeared to have started, the result of too much capacity chasing too little demand.

Such downturns are inevitable in any commodity industry because of overestimates of demand growth and underestimates of how many announced projects will actually happen. In the 24 years I’ve been covering the global polyolefins industry, I’ve seen three such downturns.

What prevented the late 2019-early 2020 downturn from happening was the pandemic. Asian and global production was cut because of lack of availability of feedstocks from refineries due to the collapse in transportation fuels demand. Polyolefins demand also boomed because of a shift in consumption patterns resulting from the coronavirus.

This latest retreat in NEA margins (NEA HDPE margins were at -$169/tonne during the week ending 4 November with PP margins at $11/tonne) is the result of the following two highlighted factors, which are followed by the context:

- The slowdown in China’s demand on container freight and semiconductor shortages that have reduced China’s finished goods exports by volume, which I’ve been highlighting since February. Exports are obviously higher this year in dollar terms because of inflation. But what counts for PE and PP demand is the volume of exports. The slowdown has been accelerated since August by the Common Prosperity pivot.

- Rising Chinese self-sufficiency on what we forecast will be a 25% increase in China’s HDPE capacity in 2021 over 2020 to 12m tonnes/year. Capacity in PP is expected to increase by 13% to 35m tonnes/year.

As we’ve just discovered with coal, never bet against Chinese government policy. Reuters wrote in this article:

“Chinese coal traders are selling cargoes at losses or trying to delay imports after Beijing’s market interventions triggered a 50% price drop that saddled them with unprofitable supplies, according to several market participants.”

If the traders had taken notice in early October of the multiple policy levers China had at its disposal to fix the coal crisis, they might not be in this situation.

Likewise, as we look to forecast PE and PP demand for the rest of this year and into 2022, don’t bet against Beijing’s policy direction.

The October 2021 macroeconomic data show that Common Prosperity remains very much on course. Investment in new construction declined for a fourth month, dropping 7.7% from a year ago as house prices fell 0.25% in October from the previous month, a bigger decline than in September, wrote Bloomberg.

China’s total lending was down by 15% on a year-on-year basis in January-October, said the latest PH report. This was lending from China’s state-owned banks and its private or “shadow” lenders.

The report argued that the fall in the availability of credit followed a pattern that began in 2018 but came to a temporary halt because of the trade war with the US and the pandemic.

Last week, the Chinese Communist Party passed a “historical resolution” cementing President Xi Jinping’s place in the country’s political history. This was seen as paving the way for Xi to have his term in office extended beyond next year, when he is due to step down having served two terms.

“This makes it very likely that Xi intends to serve for at least one more term, and probably till 2033,” the PH report added.

So, given Xi’s strong political position and the likelihood that he will remain in office for a long time to come, why wouldn’t Xi continue to pursue Common Prosperity policies?

As a reminder, the policy headlines are reducing the economy’s dependence on real estate, increasing income equality and lowering carbon emissions.

“Why wouldn’t he?” is for me a better question than, “why would he?”. In other words, Xi and the rest of China’s senior leadership team seem more likely than not to stick with building an entirely new economic growth model.

In the process, we can expect lower polyolefins demand growth than we’ve been used to over the next 10 years. I also see China increasing its PE and PP self-sufficiency as this is in line with greater self-reliance – a key tenet of another group of policies under the Dual Circulation headline.

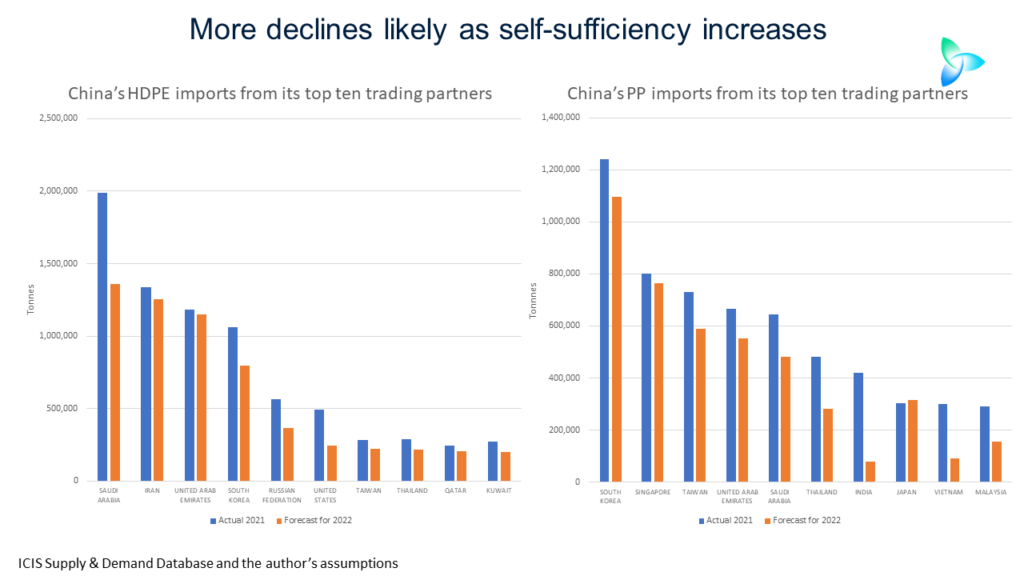

We can see the effect of a fall in demand growth combined with rising local capacities in the chart below. It shows 2020 imports from China’s top HDPE and PP trading partners versus what this year’s imports from the partners would be if the January-September 2021 trends were to continue

Remember that in 2021, HDPE demand looks set to fall by as much as 17% compared with last year as total imports slip to 6.8m tonnes from 9.1m tonnes. PP demand growth looks likely to be around 3% in 2021 compared with 2020 growth over 2019 of 13%. PP imports are heading for a 2021 total of 4.8m tonnes compared with 2020’s 6.6m tonnes.

Conclusion: the old-fashioned forecasting technique

As the coal story tells us, there is a lot of merit in the old-fashioned forecasting technique of talking to people who know what they are talking about. I am not saying that ever more sophisticated computer models don’t have their place, but I beg to suggest a very small place. Don’t forget the value of good on-the-ground market intelligence, which is the way people have successfully read markets for many, many years.

The other key message from today’s post is the critical role that government policy plays in shaping the world’s most important petrochemicals market. It has always been so. Don’t listen to anyone who tells you otherwise.