By John Richardson

Summary of today’s key points

IF THE REPORTED new problems at Yantian container port –- the third largest in the world –- had happened before 24 February, the only concern would have been further disruptions to the global container business.

Back then, I would have only worried this would have caused yet another delay to in the fall in of east-west freight rates to much more manageable levels.

Under the Old Normal, high freight rates had created a divided polyolefins world – very strong pricing and margins in Europe and the US versus comparatively very weak pricing and margins in Asia.

High container freight rates had limited the ability of Middle East and Asian producers to relieve oversupply in the dominant China market through exporting to the West. The oversupply was the result of a China demand slowdown caused by Common Prosperity and big capacity increases in China and South Korea.

But does it now even matter that much that Yantian is said by CNBC to be effectively shut down because of the coronavirus-related lockdown affecting Shenzhen –- the city of 17m people where the port is located?

Not if we are already amid a collapse in demand for Chinese exports more significant than any reductions in container-freight shipments, the result of high inflation.

Or maybe China will, as it has done in the past, subsidise its exporters to keep the China price cheap enough to sustain its export trade. There are reports of this already happening.

We must, however, also assess the effect of the latest coronavirus lockdowns on the Chinese economy. Even just a one week shutdown across the major manufacturing regions could reduce this year’s GDP growth by 0.8 percentage points.

And we need to also consider the China relationships with Russia and the West and how this might efffect Chinese trade with the West.

Poor countries bearing the brunt of high food and fuel costs

Why 24 February represents a turning point is that it of course marks the day that Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine. It was from that date onwards that demand destruction became a concern for the polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP).

Major demand destruction could already be with us because of surging energy and food costs. Cuts in non-discretionary spending in every region could be happening as people struggle with higher food and fuel costs.

In the developing world ex-China especially (we can no longer categorise China as a typical developing economy), lost demand is likely to be big. As income levels are low, bigger proportions of incomes go on food and fuel than in the rich world.

Disruptions in exports of wheat and corn from Ukraine and Russia, which have led to soaring prices, have placed millions of people in danger of severe hunger, warns the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

“At least 50 countries depend on Russia and Ukraine for 30% or more of their wheat supply, and many developing countries in northern Africa, Asia and the near east are among the most reliant,” wrote the Guardian in this article.

“Poor countries are bearing the brunt of the price increases. Many of the poorest countries were already struggling financially, with some facing debt crises, amid the pandemic,” the newspaper added.

But even in the developed world, it seems likely that discretionary spending will decline because of higher food and fuel costs – especially among lower-paid workers. Or they may be a lag effect before big declines in discretionary spending. In such an event, supply chain problems in China will in the short-term be a big deal.

As the Australian Financial Review wrote, it is not just port disruptions that are an issue for global supply chains: “Apple supplier Foxconn said on Monday it was halting operations at sites that make iPhones in Shenzhen, a city which is the equivalent of China’s Silicon Valley in the south just across the border from Hong Kong.”

Record low PP margins in Asia; and European and US margins decline

Such is the pace of events that only two weeks ago, I was applying the old thinking to an unprecedented set of events. Non-durable end-use demand for polyolefins didn’t suffer in previous economic downturns because people quite obviously must eat and so I expected history to repeat itself. A lot of PE and PP is used to wrap food.

I am no longer sure this logic holds because we face the highest rates of inflation since the 1970s. It is hard to discern any useful patterns from what happened to PE and PP demand during the 1970s period of stagflation because polymers were much less woven into our everyday lives.

Because inflation is so high, we might see people cutting back to just essential groceries e.g. “I cannot afford that packet of chocolate biscuits even though it’s on special offer.”

Anyway, focusing just on PP today, the chart below makes grim reading.

Northeast Asian (NEA) variable cost PP margins fell into negative territory last December on new Asian capacities and Common Prosperity and have remained negative.

Over the last two weeks, margins have reached record lows on rising energy costs. For the week ending 11 March, NEA margins were at minus $255/tonne.

At the beginning of March, southeast Asian margins turned negative for the first time since we began our margin assessments in January 2014. For the week ending 11 March, they were minus $24/tonne.

But, as you can see, European and US margins remain very positive. But for how much longer? Steep declines in margins have occurred over the last two weeks.

Some 18% of global PP demand goes into white goods and 12% into autos. Demand into autos was already struggling before the invasion because of the semiconductor and shipping shortages. Now demand could get even worse because of people pulling back from discretionary spending.

Around 40% of global PP demand goes into rigid and flexible packaging used to package food, other non-durable goods and durable goods.

Such is the scale of inflation that, as I said, even grocery spending may now be adversely affected across all regions.

Could China lose control of economic events? This was the question I posed in Monday’s post and needs to be considered again.

The old “China put” option of “the “worse things get, the better they will soon become” may no longer apply as no amount of China economic stimulus may help to turn around an economy affected by another wave of nationwide coronavirus lockdowns.

This hasn’t happened yet, as the new outbreaks show. As of Monday (14 March), there were only 2,125 cases reported across 58 cities in 19 of 31 mainland provinces.

But just one-week of lockdowns in major manufacturing regions could reduce China’s GDP growth by as much a 0.8 percentage points, ANZ said in the same AFR article I linked to above.

The world was very different in H2 2020 when China recovered from its last major pandemic outbreak. Inflation was a lot lower, giving Western governments plenty of leeway to launch big economic stimulus.

Cash-rich bored lockdowners were able to spend big sums on China-made game consoles, computers, washing machines and office furniture for homes.

Governments may have less room for new stimulus this time around because of high inflation.

BUT there are already reports of China relaxing lending standards for manufacturers in order to subsidise exports. The famous cheap China price may be cheap enough to allow China to maintain its export volumes.

We must, though, also consider the incredibly sensitive China’s relationships with Russia and the West.

“China’s trade with Russia reached $147bn last year, according to Chinese figures, compared with $828bn and $756bn, respectively, with the EU and US,” wrote the Financial Times in this article.

If China ends up in deep disputes with the EU and the US, sanctions might follow.

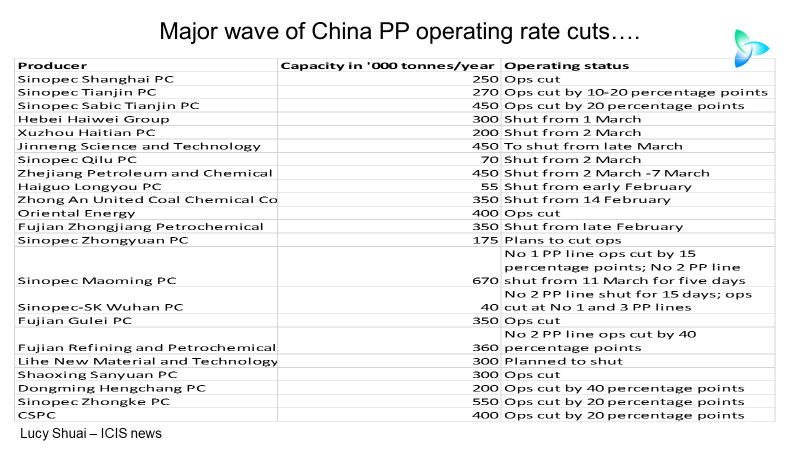

As for the here and now, the chart below is remarkable. I have never seen such a long list of operating rate cuts in China. This is from an excellent ICIS news article by my colleague, Lucy Shuai.

Lucy reports that imports are also weak. We won’t get the January-February import data until around 20 March.

China’s PP capacity is due to rise by 13% this year to 39m tonnes/year with operating rates forecast to average 81%, down from last year’s 86%. But start-ups may now be delayed with operating rates lower than we have forecast.

Global PP demand may decline by 2% in 2022

Our base case assumes 2022 global demand will grow by 3% to 85m tonnes from 83m tonnes in 2021, including a 6% increase in China’s consumption. As I discussed on Monday, however, there seems a good chance that China will see negative growth in 2022.

On Monday – and in the chart immediately above –- I assume minus 2% growth for China. This is the same percentage decline that occurred in 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis.

The rest of my downside for global PP demand in 2022 involves exactly mirroring much more recent history. I used the same percentage declines that occurred in other regions in 2020 over 2019, at the height of the pandemic, to model what could happen this year.

North America, Europe, the Former Soviet Union, Africa, Northeast ex-China and Asia and Pacific would see negative growth in 2022.

My downside results in a 2% fall in global PP demand to 81m tonnes.

In the end, this may all come down to whether there can be a diplomatic solution to Ukraine – and, hopefully, very quickly. If that were to happen, we would return to the Old Normal world of the post-pandemic recovery.

And just to stress again, the above scenario for global PP demand is purely my guesswork. For real scenario work, contact me at john.richardson@icis.com.