By John Richardson

WHEN THE GOING gets tough, the tough must get going. It will not be easy to estimate what could be higher-than-expected levels of European petrochemicals imports during the rest of 2022.

But in the context of a China that might even be in recession in H1, with its prospects of a recovery in the second half of this year looking very shaky, the extra effort necessary to estimate shifts in European trade flows is very, very worthwhile.

I will go further. Forecasting with reasonable accuracy changes in European country-by-country and product-by-product trade flows – and then responding before the competition with re-allocation of volumes to Europe – could make the difference between success or failure in 2022.

Let me give you one example – at the Europe-wide level only – of the extra revenues that might be generated in just one product by one major exporting country.

I will then discuss the areas I believe you need to focus on in order to get to an acceptably accurate view of Europe’s import requirements in 2022.

What has of course raised the prospect of more European demand for imports are energy and petrochemical feedstock shortages resulting from the Ukraine-Russia conflict.

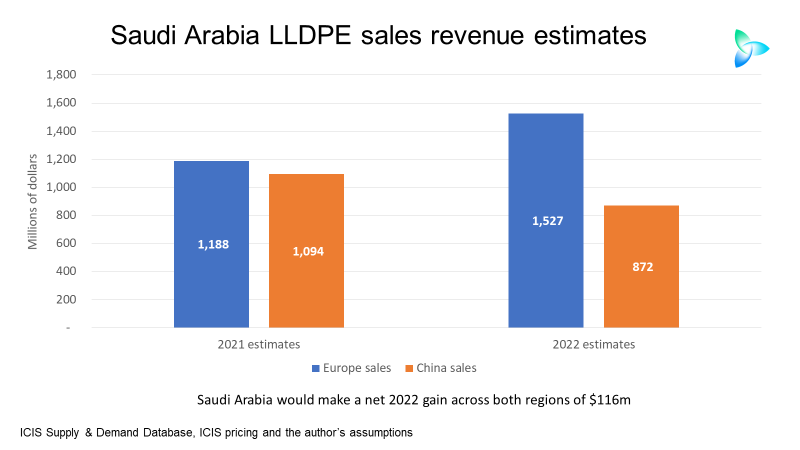

Saudi Arabia, LLDPE and the $116m opportunity

The numbers in the above chart are going to be wrong because they involve a lot of assumptions. But in terms of the scale of the potential opportunity – in, as I said. just one product and one country – this feels about right to me.

The 2021 assumptions for Saudi Arabia’s linear-low density polyethylene (LLDPE) sales revenues from the two regions are based on imports multiplied by average ICIS C4 LLDPE film grade prices in 2021 in northwest Europe (NWE) and China.

The January-February China Customs department data suggest China’s total LLDPE imports for this year could fall to 4.9m tonnes from 2021’s 5.6m tonnes.

If you add our local production estimate to net imports, you end up with 2% demand growth and a local operating rate of 87%. But China’s growth could turn negative this year as it runs its plants slightly harder, once logistics problems that have caused big rate cuts are over.

Let us factor in minus 2% demand growth with operating rates at 89%. This would leave this year’s imports at 4.1m tonnes when an estimate of export, based on the January-February data, are also included.

Local capacity in 2202 is scheduled to increase by 11%, resulting in a further rise in self-sufficiency. Capacity grew by 20% last year.

Assuming Saudi Arabia gains the same percentage share of this smaller total of imports as its percentage share in 2021 (18% – the second-highest individual country percentage), China would import 732,587 tonnes from Saudi Arabia in 2022 compared with 2021’s 992,227 tonnes.

Multiply 732,587 tonnes by the average China C4 LLDPE film price in January-March this year to get to an estimate for Saudi China revenues in 2022.

Saudi Arabia accounted for 12% of total European imports of 5.2m tonnes in 2021. Let’s guess that European imports in 2022 increase by 30% over last year to a total of 6.7m tonnes.

Let’s then say that Saudi Arabia repeats its 2021 share of Europe’s total imports – 12%. Europe would import 834,878 tonnes from Saudi Arabia in 2022 versus last year’s 642,214 tonnes.

Multiply this higher total of tonnes by the average NWE C4 film-grade price in January-March 2022 and you get to an estimate for Saudi Arabia’s revenues in Europe this year.

A big increase in European revenues would more than offset a sharp fall in sales returns from China, resulting in a net gain in 2021 for Saudi Arabia over last year of $116m.

But this assumes that Saudi Arabia only gains the same market share in Europe in 2022 that it did last year. With good enough forecasts of European imports, Saudi Arabia could push for a bigger market share.

One of the big temptations of Europe over China is much higher European pricing on tighter supply and stronger demand. This has been the case since Q1 last year.

The variables you need to consider in assessing European imports

I know I suggested last week that European petrochemicals demand weakness might be more significant than energy and petrochemicals feedstock losses, leading to insignificant or even no increases in imports.

This remains a scenario. But if anyone suggests to you that they have a crystal-clear view of European demand I would discount their opinions.

We live in such a complex consumption environment – which has been the case since the pandemic began – that no existing demand forecasting model works.

As I suggested last week, in the absence of such a model, task your sales teams to gather as much anecdotal evidence as possible from your customers and your customers’ customers.

Maybe single-use plastics demand will be more robust than I had assumed in my downside scenario last week, even if demand for discretionary goods declines on higher inflation and further supply chain disruptions.

Meanwhile, European production vulnerabilities centre on the region historically sourcing some 50% of its naphtha from Russia, around one third of its oil and approximately 40% of its natural gas.

The dependence on Russian natural gas is higher in individual countries – for instance, around 55% in Germany.

Europe is reducing its dependence on Russian energy because of the Ukraine-Russia conflict.

Our ICIS pricing team reports that most European buyers are already avoiding buying Russian naphtha – and from 15 May, just about all contract and spot purchases of Russian material will be stopped.

The availability of sufficient supplies of naphtha from alternative sources (the Middle East and the US are the other big exporters) partly depends on petrochemical production levels in Asia.

Cracker and polyolefins margins in northeast Asia (including China) and southeast Asia have been negative for several months. Margins recently hit record lows on the surge in feedstock costs and weak demand. This led to deep operating cuts, especially in China.

The rate cuts might result in spare barrels that would otherwise have been exported to Asia (Asia is a major naphtha importer) being exported to Europe.

But we need to also consider factors shaping fuel-products markets as we try and evaluate how much non-Russian naphtha will be available for European petrochemicals.

China reduced its 2022 quotas for gasoline and diesel exports in order to keep the local market amply supplied. This has tightened Asian fuel-product markets and has reportedly led to more naphtha being blended into gasoline.

As for the ability of European refiners to supply more naphtha to local petrochemicals players, this will again depend on naphtha blending values into gasoline.

Blending naphtha into gasoline increased in Q1 this year as coronavirus restrictions were lifted and people drove more.

Blending has since dipped, but the ICIS expectation is that blending will pick from mid-May/early June, barring unforeseen events. This is when the next European driving season is due to take place as Europeans take their holidays.

As always, though, we mustn’t forget the role of liquefied petroleum (LPG) gas versus naphtha prices. The usual spring and summer dip in LPG demand for heating has increased LPG’s competitiveness as a petrochemical feedstock versus naphtha.

I have yet to analyse the impact on European petrochemicals production of reduced purchases of Russian oil.

As for natural gas, the EU has set a target of reducing supply from Russia by two/thirds during the next 12 months.

But Tom Marzec-Manser, ICIS head of gas analytics, believes – as he discusses in this ICIS podcast – that European power cuts are unlikely on reductions in Russian gas supply.

Power cuts could of course shut down refineries and petrochemical plants.

Surging electricity and naphtha costs are exerting pressure on European cracker margins. Cracker operating rate cuts might also create room for more imports.

The ICIS margin chart below shows how European cracker margins briefly dipped into negative territory in early March before seeing strong recoveries.

Conclusion: every market anecdote will help

Yet another piece of the jigsaw puzzle is the absence of Russian PE and polypropylene (PP) imports in Europe. While Russian polyolefins surpluses play a small role in the global picture, they are more significant for some countries in Europe.

Our ICIS Supply & Demand Database will tell you the European country-by-country dependence on Russian resins in 2021.

As for the missing naphtha piece of the puzzle, this is hugely, hugely complicated. It may even be impossible to accurately predict how extra naphtha from non-Russian sources will be available for Europe, but we need to try.

What helps us move closer to understanding naphtha supply is this video from Ajay Parmar, the ICIS oil and naphtha analyst.

Every market anecdote on Europe’s petrochemical feedstock situation from our ICIS team of editors will also help you edge closer to an integrated view of the future.

As I said, the tough need to get going to win the rewards in what are exceptionally difficult market conditions. For example, consider this: China is normally the world’s biggest polyolefins import market with Europe in second place, but maybe, just maybe, these positions will be reversed in 2022.