By John Richardson

MANY OF US have known nothing during our working lives other than an almost constantly booming China. I believe that is making it difficult for some people to accept that today’s downturn may not be as short-lived as previous downturns during the past 30 years.

But data on the number of empty apartments, real-estate debt levels and a rapidly ageing population show that, even if Beijing succeeds in stabilising the property market (it probably will), there can be no return to the heady speculation of 2009-2021.

We know from ICIS chemicals demand data, when linked with official government numbers on lending, that it was this heady speculation that led to often double-digit rates of chemicals demand growth annually, between 2009 and 2021.

“The world’s most populous country has reached a pivotal moment: China’s population has begun to shrink after a steady, yearslong decline in its birth rate that experts say will be irreversible,” wrote the New York Times in a 16 January article.

“The government said on Tuesday that 9.56m people were born in China in 2022, while 10.41m people died. It was the first time deaths had outnumbered births in China since the early 1960s,” the newspaper added.

Regular readers of this blog would know that I’ve been warning about China’s demographic crisis for 12 years. This is a historical first: Never before has a country so poor become so old so quickly.

Now that the property bubble has popped, how will China pay for its old people, given that a major source of funding for healthcare and pensions came from revenues from land sales?

Revenues soared during the property boom as land prices rose. Now the opposite is happening.

“Changes in the labour market are leading to a rapid increase in the number of workers entering the less secure informal economy, while employment in the formal manufacturing sector, once the foundation of China’s employment, is falling,” wrote the US-based Center for Strategic and International Studies in a May 2022 study.

“Moreover, continued inequality in access to education and healthcare means that many employees lack the capabilities needed to excel in the high-skilled, high-wage jobs that are appearing as China’s economy seeks to reach high-income status. Automation is also increasing in China and could further reduce employment opportunities for a sizeable portion of the workforce in the years ahead,” said the study.

The study reminds us there are no guarantees China will escape its middle-income trap, made deep by its ageing population. Lack of access to high-value technology because of the geopolitical split with the US has further increased the depth of the trap.

These long-term challenges also matter in the short term, setting ever-lower annual speed limits on the ability of China’s economy to bounce back from more temporary setbacks, such as the after-effects of the country’s zero COVID policies.

After-effects of zero COVID include increased rural economic inequality, high youth unemployment and lack of trust in the consistency of government policies following the sudden reversal of zero-COVID-

Lack of confidence could limit the extent of the bounce back in consumer spending and business investment during 2023.

Another uncertainty relates to when China will get on top of its exit wave.

Will this be soon after the Lunar New Year (LNY) holidays, which runs from 21 January until 27 January this year? Or will mass migration during the holidays represent a “super spreader” event? And might China see a second or even a third wave of the virus, as has been the case in other countries?

China’s chemicals prices have seen modest increases so far in 2023, on the theory that Beijing will get on top of its exit wave soon after 27 January – and that this will be followed by a strong economic rebound.

This, to me, is a sign of what I highlighted at the beginning of this post: The difficulty in accepting that this time might be different because few, if any, of us have experienced anything other than an almost constantly booming Chinese economy.

Spreads data matter more than price movements

As I said, China’s chemicals prices saw modest increases during the first two weeks of January 2023 on traders reportedly building bigger stocks ahead of a forecast post-LNY demand rebound.

But as I was taught many years ago when I was training to become a chemicals analyst, the value of tracking chemicals price movements by themselves is very limited. What matters more are the relationships of chemicals prices to feedstock costs.

Remember: Until China’s spreads between chemicals prices and raw-material costs have recovered to their historic long-term averages, there would have been no full recovery.

The above chart uses CFR China high-density polyethylene (HDPE) injection grade and CFR Japan naphtha costs as an example. But if you parse the China data for all the gaseous and liquid chemicals and polymers the trend is the same: Spreads have never been this low since our price assessments began.

HDPE injection grade spreads averaged just $210/tonne last year compared with the annual average 1990-2021 spread of $495/tonne.

There was a slight pick-up in spreads during the first two weeks of January to $235/tonne. But spreads need to increase by a further 111% – back to the long-term average of $495/tonne – before we can say the market has fully recovered.

Consumer confidence is hard to predict

Despite all the negatives, the enormous relief of zero-COVID being over might lead to a consumer spending splurge – assuming again the exit wave is brought under control early enough in 2023 to make a significant difference.

Also, large parts of the economy were shut during zero COVID. Reopening will inevitably lead to a big pick-up in economic activity from a low base. We are already seeing this in the big cities as subway traffic resumes, restaurants reopen and express parcel deliveries increase.

It is therefore perfectly possible that our base case scenario in the chart below – an average 4% increase in China’s PE demand across the three grades in 2023 – happens. Equally feasible outcomes are my two downsides of 2% and 5% negative growth.

The next chart is a reminder of the major global consequences of either of these three outcomes in 2023.

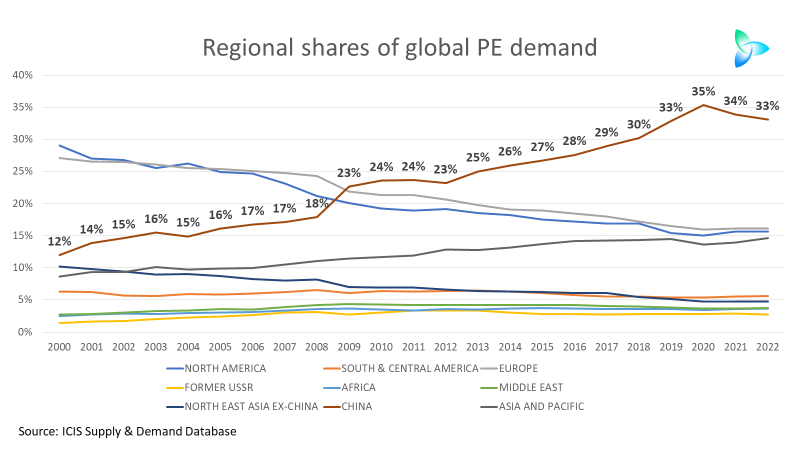

China’s percentage share of global PE demand jumped from just 12% in 2000 to 33% in 2022.

As I did with polypropylene (PP) last week, let’s take these three scenarios for China’s PE demand in 2023 and put them into the global context.

As with PP, I’ve left growth in other regions in my two downsides unchanged from our base case. This is unrealistic as a weaker-than-expected China would have negative effects on demand elsewhere, because of China’s big role in driving the economy.

As always, my scenarios are for demonstration purposes only and don’t represent the proper scenario work ICIS provides via our analytics and consulting services.

But China downsides by themselves would still have major global consequences.

Even our base case sees global PE capacity in excess of demand at 22m tonnes in 2023 compared with a 10m tonnes/year annual average in 2000-2022. We forecast this year’s global operating rate at 79% versus the average annual 2000-2022 operating rate of 86%

Downside One would see 28m tonnes of excess capacity and a global operating rate of 77%; Downside Two would be 30m tonnes and 76% respectively.

Conclusion: Forecast, reforecast and reforecast again

This PE story wouldn’t be complete without the chart below.

China’s net PE imports in 2023 could total either 12.9m tonnes, 11.2m tonnes or 9.5m tonnes, depending on the same three demand-growth outcomes and different operating rates.

Estimating and constantly re-estimating China’s imports will be important in 2023, as China accounts for some 50% of global net imports among the countries and regions that import more than they export.

Frequent updates on Chinese demand are also essential, grade by grade and end-use application by end-use application as the macro factors highlighted above play out.

Every other market will, of course, also count. Markets outside China will become more important in the event of negative Chinese growth and big declines in its net imports.

We will get through this crisis through deep and constantly updated global analysis of demand, trade flows and production. As I suggested last week, companies should consider Demand and Supply Workshops that take place very frequently.