By John Richardson

THE PHRASE “pushing on a piece of string” might best describe the logic behind calls for another round of big economic stimulus in China. Any extra money pumped into the economy could be largely saved rather than spent because of weak consumer confidence resulting from an ageing population and the end of the property bubble.

This is assuming that China has the wiggle room for big stimulus given the scale of its debts. Furthermore, we cannot be sure if it has the appetite or not for further big stimulus because it is attempting to build a new economic growth model.

Nevertheless, the calls still came in earlier this week for more stimulus, following the release of the official second quarter GDP growth data.

“China’s economy lost momentum in the second quarter, with gross domestic product expanding 0.8 per cent against the previous three months as falling exports, weak retail sales and a moribund property sector weighed on growth,” wrote the Financial Times in this 17 July article.

The FT added that the weak performance had led to more calls for the “playbook of the past” – big monetary and fiscal stimulus to boost property and infrastructure.

Putting aside my doubts about the scale and effectiveness of future stimulus, there is nothing China can do about the challenges facing its exports. Even without the impact of inflation on China’s exports of manufactured goods, there was always going to be a cycle of heavy spending on goods and into services once the pandemic had passed its peak.

Who wants to stare at a second new laptop you don’t really need when you can instead get on a flight to Ibiza from London?

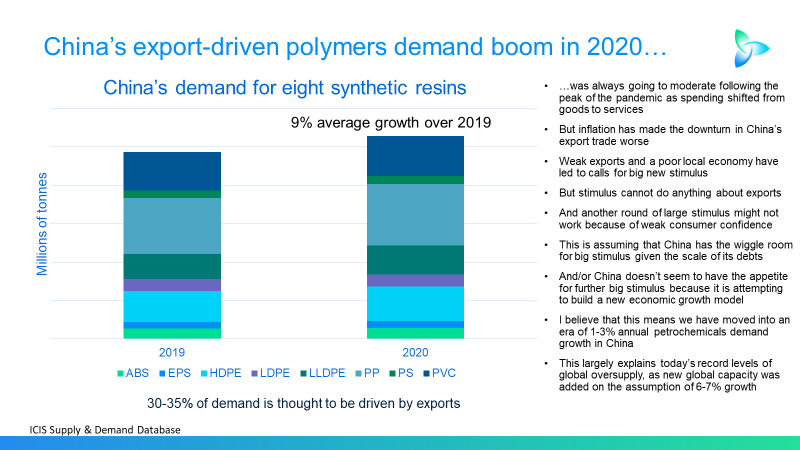

The chart below shows the uptick in China’s demand growth for eight of the major synthetic resins in 2020, the height of the pandemic.

Guesstimates are that 30-35% of China’s polymers consumption is driven by local petrochemicals production used to make exports and imports of polymers that are re-exported.

The comments on the chart summarise my thoughts above and in the rest of this post.

The chart below, from Bloomberg compilation of China’s General Administration of Customs data, shows the fall in dollar terms of China’s exports and imports since June 2021. Exports in dollar value were down by 12.4% in June 2023, on a year-on-year basis.

China can do nothing about the pace at which interest rates will eventually be cut in the West.

The lag effect of the interest rate increases could continue to dent demand for China’s exports for a few more years.

A new economic growth model

Another important point is that China’s government policy direction appears to have changed. It seems to no longer be pursuing growth for the sake of growth at the expense of income inequality, the debt problem, soil and water pollution and increases in carbon emissions inconsistent with its push towards net zero.

Another objective appears to be is the push for hi-tech self-sufficiency in response to greater geopolitical tensions with the US.

“Xi Jinping does not define economic success in terms of GDP growth,” said Arthur Kroeber, founding partner and head of research at Gavekal Dragonomics, in this 18 July FT article.

Kroeber said that China instead now defined success as tech self-sufficiency. Adherence to this policy is called dingli, or “maintaining strategic focus”.

There could still be more stimulus on the way however, during the remainder of this year that could improve petrochemicals demand.

January-May data, for instance, suggested that high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and polypropylene (PP) demand could fall by 3% and 1% respectively in 2023. But stimulus might improve the picture.

The Economist in this 17 July article said that sales of flats or condos fell by 27% in June as compared with a year earlier.

Condo sales were running well below the pace economists said was justified by urbanisation and the widespread desire for better accommodation, said the magazine.

This suggests there might be room for targeted real-estate stimulus that doesn’t re-inflate the property bubble.

There are signs that the government is pulling back on its crackdown on tech platforms. This might generate more employment. Youth unemployment was at 21.3% in June with, of course, young people predominantly filling new job posts in tech.

“Liu Guoqiang, deputy governor of the People’s Bank of China, said most countries took a year to recover from the end of Covid restrictions. China only abandoned pandemic controls six months ago,” said the same 18 July article in the FT.

A former Wuhan government official was also quoted in the 18 July article as saying that inventory building during the pandemic was behind the fall in China producer prices in June.

But I l keep coming back to the “pushing on a piece of string” analogy. Any recovery during the rest of the year will be moderate relative to previous economic rebounds, I believe. The chart below is a reminder of why.

No country the size and with the economic importance of China has seen a demographic crisis on this scale before.

The trend line shows the births per woman fell from the peak of 7.5 in 1963 to just 1.2 in 2022. China’s births per woman first fell below the population replacement of 2.1 rate way back in 2001 and have remained there ever since.

Economic growth is being dented by the fall in family formations since 2013. This is the result of both the greying of the population and the higher number of boys born compared with girls.

“New family formations in China have been declining since 2013 alongside the falling marriage rate, the by-product of decades of China’s one-child policy,” wrote the Council on Foreign Relations in this 21 March article.

The decline in the growth of new families must be affecting housing demand, as is the end of the old government “put option”.

Beijing had guaranteed that property prices would never fall, making investment in multiple properties a gamble worth taking. But since 2021, real estate prices have fallen, badly denting confidence in a sector that’s worth some 30% of China’s GDP.

There must be pressure to save more to cover rising pension and healthcare costs resulting from an ageing population.

The tried and tested approach to boost GDP was investment in infrastructure. But now:

- Local governments, which are responsible for 70% of total government spending, are struggling to raise money for new bridges and roads because local government financing depends on rising land prices, and land prices are falling.

- Most of the infrastructure that needs to be built in China’s most-populous provinces has been built. Therefore, when the remaining infrastructure that needs to be built is built in the less populated provinces, the economic multiplier effect will be more muted.

Conclusion: Adjusting to the new China

I still get the impression that some people are waiting for yet another economic bazooka on the scale of 2009, when China rode to the rescue of the global petrochemicals industry during the global financial crisis.

So, let me stress again: We need to adjust to a new China where big stimulus-led growth is a thing of the past.

And there are two possible long-term economic outcomes:

- China successfully builds a new growth model involving a shift to higher-value manufacturing and services. This justifies the increase in its wage costs resulting from a rapidly ageing population. “Higher-value” is centred on sustainability as China reduces local pollution while meeting its net-zero target.

- China fails to build a new growth model and its economy struggles.

Under either outcome, petrochemicals demand growth must surely, in my view, be substantially lower than in the past.

You might say, “Come on! Everyone’s always known that China’s growth would slow down as its economy matures.”

Here’s the thing, though: Only three years ago, the consensus was that China’s petrochemicals markets would grow at 6-7% per year just about in perpetuity.

Now the consensus is swinging to back my long-held view of growth slipping to 1-3% year from high single digits to double digit growth in 2000-2021, depending on the commodity.

This will make a huge difference in today’s oversupplied markets as a lot of the new global capacity due to start-up before 2025 was based on a 6-7% growth for China.