By John Richardson

LET’S PAUSE after H1 to consider where the key China polyethylene (PE) market, by far the most important in the world, stands.

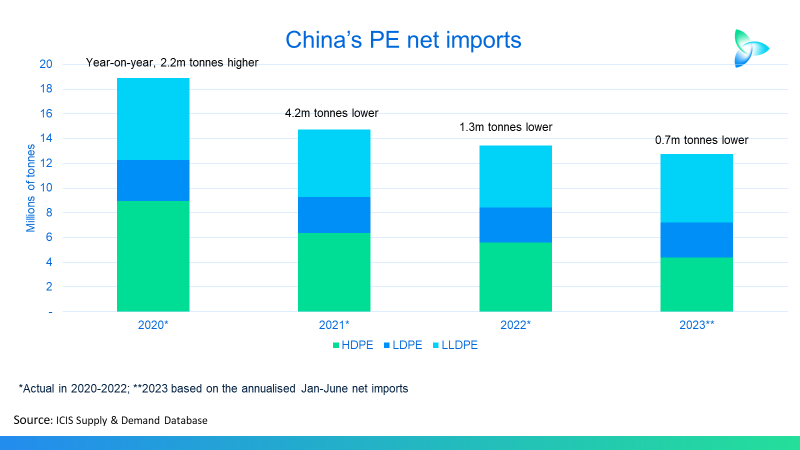

I was taught many years ago that a rough and ready way of estimating demand is to add net imports in any net import country to local production – hence, the above slide. I’ve been providing these slides on the blog for the last five years using the hugely valuable ICIS data.

What you can see is actual demand for the three grades of PE in China in 2020-2022 versus what the January-June 2023 China Customs net imports plus our estimates of local production suggest for the full year 2023.

Meaning, you add the two numbers together for January-June 2023, divide by six to get a monthly average and then multiply by 12.

If the second half of this year exactly mirrors H1 2023, total PE consumption would grow by 0.5m tonnes during the full-year 2023 versus 2022. That would be an average 1% rise across the three grades versus expectations out there of growth of around 4%, which would deliver an extra 1.6m tonnes of volume.

But we know that this is very unlikely to happen as the future seldom entirely reflects the past.

If we parse the data, we find that the outlook for high-density polyethylene (HDPE) has improved over the last three months.

The January-April data indicated a 4% decline in full-year demand, January-May a 3% decline and January-June a 2% decline. Perhaps we will end the year with positive growth.

And the further good news is that the January-June 2023 numbers suggest a 3% increase in linear low-density PE (LLDPE demand) compared with the decline indicated 2% by January-May numbers.

The latest data also suggest 5% growth low-density (LDPE) demand this year. This would follow negative growth in 2020-2022.

What you can see above, though, is just a snapshot in time and is just one scenario. I recommend building multiple scenarios for the final outcomes of China’s PE demand in 2023, using our excellent analytics team in China and our consulting team.

The slide below should also be taken with a pinch of salt. It suggests that, based on the annualised January-July China Customs net imports, China’s total PE imports in 2023 could fall by 0.5m tonnes.

HDPE net imports could see a big decline from 5.6m tonnes last year to 4.4m tonnes in 2023. But the H1 2023 data suggest LLDPE imports are heading for a 10% rise this year to 5.5m tonnes. LDPE net imports look as if they will be almost flat at 2.9m tonnes.

A secular versus a short-term China demand shift

One can argue, when examining today’s chart on China’s PE demand that all we have seen in weak in the HDPE market is a temporary lull in China’s booming demand story, with LDPE and LLDPE indication the direction of travel.

Perhaps you will say that a slowdown from 2020’s demand growth of 10% across all the grades was always going to stretch out over a few years. What made 2020 a banner year was the surge in demand for China’s exports.

Rich and bored lockdowners in the West bought large quantities of durable goods during the height of the pandemic in 2020.

Spending on durable goods was always going to decline once the pandemic had passed its peak. The decline has been made worse by the rise in inflation and interest rates.

As I discussed in my 25 July post, however, the group of “wise old” China hands who are among my contacts believe the shift in the Chinese economy is secular rather than short-term. I agree.

This secular shift began in August 2021 when Beijing appears to have become more committed to building a new economic growth model. This led to the deflation of the real estate bubble.

As every year passes, the impact of China’s ageing population on economic growth increases. We must also evaluate the impact of high youth unemployment on growth, which reached 21.3% in June.

I therefore believe it is essential that you build a scenario where what we have seen in 2022 and H1 this year points towards a secular and long-term shift to lower growth.

And I do worry that we might have seen overstocking in LDPE and LLDPE which is behind their positive H1 2023 growth numbers.

This doesn’t mean that this should be your only scenario. But it’s my strongly preferred scenario.

The same should apply for what happens to China’s net PE imports in H2 this year.

Today’s second chart will of course need to be constantly updated based on changes in local production and the affordability of imports versus domestic PE output. Again, get in touch with our China analytics team for this level of granularity.

But it again all comes back to the spreads and margins

“Chinese stocks staged their biggest one-day rally since November after a call by China’s leaders for strong ‘countercyclical’ measures to support the world’s second-largest economy, despite what economists said was a lack of detail in Beijing’s plans,” wrote the Financial Times in this 25 July article.

The article then goes onto detail the lack of detail in China’s latest stimulus package. But regardless of the substance and scale of the new stimulus, please consider this from my 20 July blog post:

THE PHRASE “pushing on a piece of string” might best describe the logic behind calls for another round of big economic stimulus in China. Any extra money pumped into the economy could be largely saved rather than spent because of weak consumer confidence resulting from an ageing population and the end of the property bubble.

This is assuming that China has the wiggle room for big stimulus given the scale of its debts. Furthermore, we cannot be sure if it has the appetite or not for further big stimulus because it is attempting to build a new economic growth model.

What would be highly unusual is if PE demand growth returned to its long-term historical strength in 2023 while spreads and margins remained where they are today. Let’s first look at the latest spreads data from my 24 July LinkedIn post.

Also consider this chart from the same LinkedIn post. This shows actual price movements since the downturn began in January 2022.

At no point since January 2022 has pricing increased more than the rise in feedstock costs. And in March 2022, prices remained flat despite a sharp price in naphtha.

Most recently, from the start of June until 24 July, pricing was flat as naphtha costs edged higher. This indicates a lack of producer pricing power in a very, very oversupplied market.

Consider the table below the pricing chart. China’s HDPE spreads would have to recover by 101% from their 1 January 2022 until 24 July 2023 level to return to their 1993-2021 average.

LDPE spreads would have to rise by 43% and LLDPE spreads would need to be 76% higher. This means that we would have to see a 68% average recovery in spreads across the three grades.

The final chart for today showing our annual Northeast Asia PE integrated naphtha-based variable cost margin assessments is even more shocking.

You might think that things are looking slightly brighter because this year’s margins are back in positive territory.

But this is only because PE and co-product price declines have been less than the steep drop in naphtha costs. Naphtha is down on weaker demand for crude due to the weak Chinese and global economies.

Margins from 2014 until 2021 averaged $451/tonne. But from 4 January 2022 (when the downturn began) until 2023 July, they averaged just $13/tonne. So, we need a 3,423% improvement in margins to get back to the 2014-2021 average.

Conclusion: Very strange things can sometimes happen

It could be that we see spectacular recoveries in PE spreads and margins in H2 2023. This would indicate a rebound in China demand growth to the “old normal” of the mid -to high single digits.

While events can often surprise us, I cannot recall having before seen such a rapid recovery in spreads, margins and demand in any regional chemicals market and in any commodity.

As I said, please, please don’t overstretch yourselves, be cautious out there and make sure you’ve conducted proper scenario planning.