By John Richardson

HAVE some companies in the polyester chain in China worked themselves into a position where they are “too big to fail?”

And might capacity additions carry on, despite Beijing’s attempts to rein-in further additions to already oversupplied industrial sectors such as the polyester chain?

These were some of the questions the blog was left pondering after it attended, and spoke at, last week’s ICIS Asia PET and Polyester Conference in Jakarta.

Of course, most of us usually apply the phrase “too big to fail” to the Western financial institutions that were so leveraged-up when the Lehman Bros crisis began that the whole financial system might have collapsed if they had gone under. Thus, they were bailed out and now, thanks to quantitative easing, are taking on too much risk again.

But here’s the parallel…

In China, there appears to have been a frantic race to add paraxylene (PX), purified terephthalic acid (PTA), polyethylene terephthlate (PET) resin and polyester fibre capacity when the money was available, during China’s huge 2008-2009 economic stimulus programme. And since July of this year, when Beijing launched another stimulus package, the starting gun seems to have sounded again.

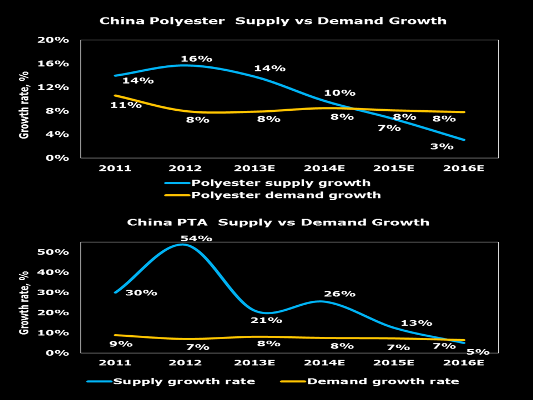

“In terms of standard supply and demand analysis, you cannot make sense of it,” said one delegate on the sidelines of the conference. He was referring to how PTA and polyester capacity growth in China in 2013 and 2014 has been away above demand growth (see the above charts prepared by my ICIS colleague Becky Zhang – our Asian ICIS pricing fibre intermediates editor ).

Producers everywhere, of course, often build capacity ahead of demand on the assumption that the long-term outlook for growth looks strong.

But rising wage costs and an appreciating RMB have been undermining the competitiveness of China’s PET bottles and film makers and textiles and garments producers for several years now. This is having a negative impact on demand all the way up the polyester chain to PX and beyond.

Chinese producers, however, assumed that if they built big when the financing was available, they would be able to force overseas competitors with inferior economies of scale to the wall in the event of weaker downstream demand growth.

This might end up being the case: South Korean PET resin operating rates are said to have fallen to 50-60% in 2013 compared with 95% last year because the South Koreans are finding it harder to export to China.

It also seems as if some Chinese producers were worried that if they didn’t follow the herd and expand when they had the opportunity, their scale relative to their domestic competitors would decline.

This decline in scale might have reached the point where local governments wouldn’t have any need to protect a company from consolidation, once the inevitable pressure from the central government for rationalising capacity began (many people in China’s polyester industry appear to have known for several years, that, at some point, Beijing would have to do something about over-investment in the sector and in manufacturing in general. That point now appears to have been reached).

“The bigger a company is the more important it becomes for generating local GDP growth, jobs and tax revenue for a local government. As a result, the really ‘big boys’ will get maximum resistance from local officials against central government consolidation efforts,” said a second delegate on the sidelines of last week’s conference.

As we discussed earlier this week, provincial, city and town governments have lots of personal and fiscal motives to push against Beijing’s new reform agenda. Incentive systems will very likely have to be rebuilt from scratch for reforms to work and this could take a considerable length of time.

Thus, the big producers might have bought themselves several years’ worth of protection from being forced to merge or scrap their operations.

And meanwhile, might capacity additions carry on? Quite possibly yes – until or unless a new and effective local government incentive system is created.

Another question that the blog was left pondering at the end of the conference was: What does this mean for the rest of Asia?

It means, as we said, lower operating rates in countries such as South Korea – not only because of reduced to export to China, but also because China will itself increasingly become an exporter.

The easy availability of finance has meant that many of the new plants up and down the polyester chain in China are not only big in scale; they also have state-of-the art technologies.

The blog was therefore distressed to hear from some speakers at the conference of plans to aggressively expand capacities in countries such as Indonesia.

This is a bad idea we think, at least for the next few years.