The global commodity super-bubble is coming to an end, as I describe in my latest post for the Financial Times, published on the BeyondBrics blog

It is exactly a year since we forecast that a Great Unwinding of stimulus policies was underway, due to a major slowdown in China. As we warned on beyondbrics:

Oil and commodity prices are falling sharply as supply/demand once again becomes the key driver for prices; the US dollar is strengthening and liquidity is tightening across the world; equity markets risk sharp falls, as investors realise they have overpaid for future growth and rush for the exits; China’s economy is slowing fast as the new leadership implements the World Bank’s ‘China 2030’ plan; interest rates are becoming volatile as some investors seek a ‘safe haven’, while others worry that stimulus policy debt may never be repaid.

Today, it is clear that risks are rising in all these areas. And fewer people now believe that the problems can be magically wished away by a further round of stimulus – even if this was economically and politically possible.

Our view is that markets are beginning to recognise that China fooled the world with its stimulus programme. Contrary to popular belief, China did not suddenly become middle-class by Western standards in 2009. Instead, aided by developed country stimulus, its easy-lending policy created a global commodity super-bubble to rival, and perhaps even exceed, the US dot-com bubble in 2000 and the US subprime bubble in 2008.

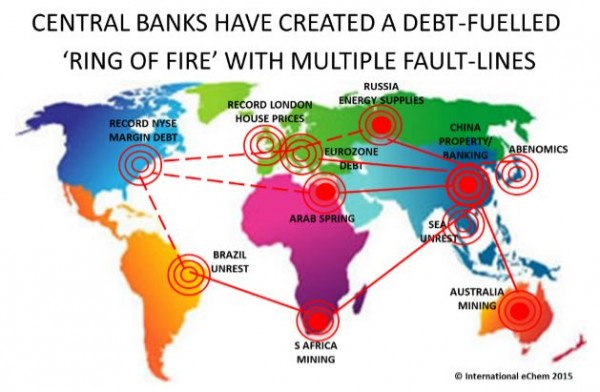

China’s new leadership have been busy reversing this policy since coming into power in March 2013, following the strategy set out in the ‘China 2030’ plan. In turn, this has turned the world upside-down for commodity exporters, who had borrowed heavily to boost production in order to meet China’s supposedly ever-increasing demand. This is now creating a debt-fuelled ‘ring of fire’ connecting Latin America, South Africa and South East Asia with Australia, the Middle East and Russia.

It was of course comforting for investors to believe that the start of the downturn in May 2013 was somehow due to a ‘taper tantrum’, caused by a concern that US interest rates might not stay at zero forever. Comforting, but unrealistic. Instead, it was markets starting to recognise that China’s consumption boom was only temporary, and mainly due to government stimulus spending.

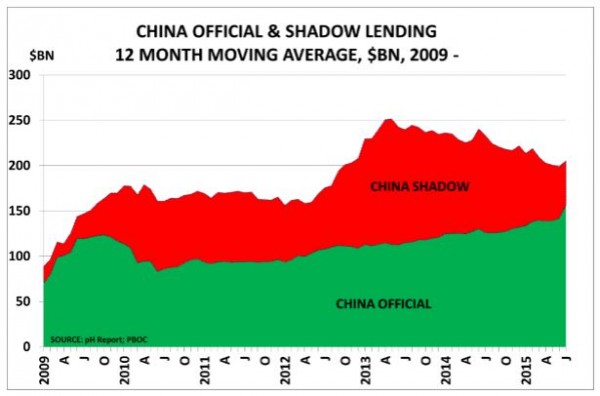

Understandably, investors had not wanted to ask too many questions about the underpinnings of China’s boom, as this had stabilised global markets and the economy from 2009. But in reality, it was built on a threefold increase in total social financing through state and shadow banks. Official estimates show lending jumped from $83bn in December 2008 to a peak of $252bn in May 2013 (on a 12-month moving average basis). Since then, lending has fallen by nearly a fifth to average just $202bn in July. Bubbles deflate like balloons when the lending that created them starts to reduce.

The problem with the lending stimulus was simply that it was unsustainable. By the first quarter of 2013, each $1 of credit was adding the equivalent of just 17 cents to Chinese GDP, down from 29 cents the previous year and 83 cents in 2007. And as the FT noted last October, China’s debt service bill is now running at around 17 per cent of 2015 GDP, or $1.7tn, almost equal to India’s total GDP.

Of course, markets and policymakers never move in straight lines. We will almost certainly see further volatility in coming weeks. Many investors have, after all, been taught to ‘buy on the dips’ on the assumption that any downturn will force policymakers to add more stimulus. But the problem with this strategy is that the size of today’s global commodity super-bubble surplus is just too large relative to demand. As the International Energy Agency’s August report noted for oil markets, “global supply continues to grow at a breakneck pace“. As a result, it warned that “2H15 sees supply exceeding demand by 1.4 mb/d, testing storage limits worldwide”.

Thus market developments seem to be confirming our long-held view that oil prices will return to their historical levels around $25/bbl. Our latest pH Report highlights three key implications of this development for investors and companies:

- Deflation is looming in the major economies as commodity prices fall and China’s export prices are further reduced by its devaluation.

- We fear that the end of the commodities super-bubble will lead to major corporate bankruptcies, as occurred at the end of the dot-com and subprime bubbles.

- We worry that protectionism is likely to spread, as governments become concerned to protect employment.

The position is not helped by the high levels of margin debt now existing on the New York Stock Exchange. In real terms, these are higher than at previous margin peaks in 2000 and 2007 – neither of which proved to be good times for buying stocks.

Buying on margin is a very dangerous game, as high levels of margin debt create a vicious circle when prices fall. As we have seen in recent days, this means speculators are forced to sell into weakness to meet margin calls from their brokers. Those who have chased London house prices into the stratosphere may come to learn a similar lesson, as the Chinese buyers who have powered demand for new-build houses in the city centre exit their positions.

Paul Hodges is chairman of International eChem and publisher of The pH Report.