Brazil, Russia, India and China disappoint as manufacturers face investment demands of EVs © Bloomberg

Less than a third of China’s 31,000 auto dealers were profitable in the first half of 2019, as I describe in my latest post for the Financial Times, published on the BeyondBrics blog

Auto markets in the Bric countries are facing two major challenges. The first relates to the downturn already under way in the two largest markets, China and India, where 2019 sales seem likely to be at least 10 per cent below the previous year’s levels.

The second is the need for manufacturers and parts suppliers to spend billions of dollars on the transition to electric vehicles in order to meet Chinese government production targets in 2021-23.

It therefore seems probable that winners and losers will emerge over the next 18 months, as companies along the value chain find themselves short of cash to fund the new investments required.

China’s downturn is particularly important as sales in Brazil, Russia and India have already fallen by 20 per cent since peaking in 2012, as the chart below shows (January-November basis). Chinese sales have been in a downturn for more than a year, and the impact is broadening along the supply chain.

As Automotive News reported: “We knew China had been in a prolonged auto sales slump, and we knew the market was under pressure from tougher municipal and provincial emissions standards. Now, we’re seeing how these factors are devastating dealerships, to the tune of half of them being sold and several hundred being driven out of business.”

Less than a third of China’s 31,000 dealerships were profitable in the first half of 2019. The downturn is particularly bad news for western manufacturers, whose global profits have depended on China volumes.

US brands are worst hit, with January-November sales down 23 per cent due to frictions caused by the US-China trade war. General Motors reported third-quarter China sales down 17.5 per cent, continuing their slide since the second quarter of 2018, with sales also hit by strong competition in the key mid-priced sport utility vehicle segment. Ford saw its third-quarter sales fall 30 per cent — accelerating the downturn that began at the end of 2017.

French brands are having a difficult time, with volume down 54 per cent in January-November. Seventy per cent of Peugeot, Citroën and Renault’s dealerships were lossmaking in the first half of last year.

Korean brands were down 15 per cent, and even German brands had no growth over the previous year.

The problem is magnified by the fact that China’s market has seen rapid growth since 2008. Many companies and dealerships therefore assumed that the sales ramp-up from 550,000 vehicles a month in 2008 to 2m a month by 2016 was somehow “normal”. They have no concept of a slowdown, or how to survive it.

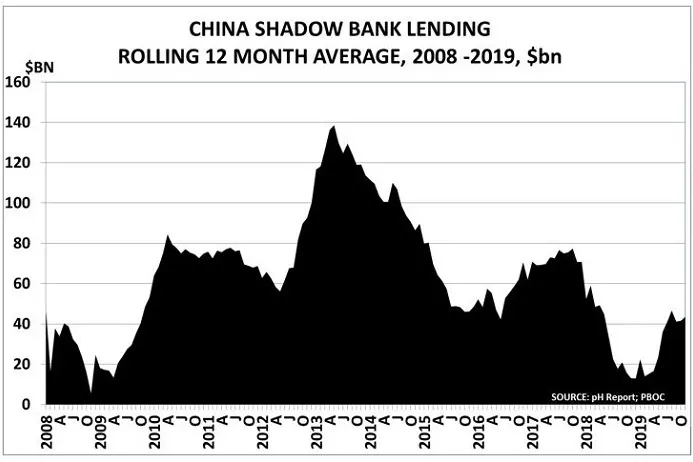

The downturn is likely to intensify as the government continues to squeeze the shadow banking sector and hence the property market. As the chart below shows, shadow lending remains well down on its earlier peaks, averaging just $67bn a month in the 10 months to October. This means, as we noted here a year ago, that “buyers can no longer count on windfall gains from property speculation to finance their purchase”.

As Reuters notes, the scale of the previous stimulus-driven growth also means that today, “much of the urban middle class has already purchased a vehicle. Household ownership rates were nearing 50 per cent in the provincial-level cities of Beijing and Tianjin and the wealthy province of Zhejiang by the end of 2017 . . . Pushing ownership further down the income scale in urban areas as well as out into the poorer countryside is harder without generous tax incentives, plentiful credit and fast growth in incomes.”

Sales in the other Bric markets are also slowing. India’s sales were down 13 per cent at the end of November, while in Russia the industry is now forecasting a 2 per cent decline. Even in Brazil, industry trade group Anfavea has reduced its growth forecast to 8 per cent, due to the slowing Latin American economy.

The downturn creates a major dilemma for the industry, as it coincides with the need to commit to major new investments in EV manufacture.

China is proposing to set a 14 per cent target for EV production in 2021, rising to 16 per cent in 2022 and 18 per cent in 2023. Similarly, the industry ministry has called for EVs to be 25 per cent of total new car sales by 2025, and announced that “regions with ripe conditions have our support if they establish trial projects to establish no-go zones for gasoline-powered vehicles and replace them with new energy vehicles in the urban public transport system”.

Companies therefore have to move forward with EV investments, even though their profits are under pressure from the sales downturn.

Volkswagen, for example, is planning to open two Chinese EV factories this year with total capacity of 600,000 cars, and aims to produce 11.6m EVs in China by 2028. Tesla is opening capacity for 250,000 cars and plans to double production in the future.

With other manufacturers following suit, some in the industry expect EV prices to fall below those for internal combustion engines within the next two years, which would further accelerate the transition.

The industry is therefore faced with a stark choice. The need to commit to EV manufacture means there is no “business as usual” strategy for either manufacturers or parts suppliers. Those who decide to conserve their cash risk finding themselves without the relevant products and services in the world’s largest auto market.

Paul Hodges publishes The pH Report.