Beijing has a population of 21.5 million, but you wouldn’t know it from this BBC video from last Thursday. Normally busy streets and transport systems are eerily empty, with food deliveries often the main traffic on the roads.

It’s the same picture in industry, with the Baidu Migration Index reporting only 26% of migrant workers had returned to work across 19 sample cities by 19 February, compared with 101% a year earlier.

The position is even worse in Hubei province, the most important industrial manufacturing province in the country, as this South China Morning Post video, also from last Thursday, confirms.

China is clearly nowhere near getting “back to normal”, as the SCMP reports:

“Choked off from suppliers, workers, and logistics networks, China’s manufacturing base is facing a multitude of unprecedented challenges, as coronavirus containment efforts hamper factories’ efforts to reopen.

“Many of those that have been granted permission to resume operations face critical shortages of staff, with huge swathes of China still under lockdown and some local workers afraid to leave their homes. Others cannot access the materials needed to make their products, and even if they could, the shutdown of shops and marketplaces around China means demand has been sapped.

“Those who manage to assail the challenges, meanwhile, have found that trucking, shipping and freight services are thin on the ground, as China’s famed logistical machine also struggles to find workers and navigate provincial border checkpoints that have popped up across the country.”

Cash-flow is also drying up at thousands of companies, large and small. It is now a month since the emergency began. Bloomberg reports, for example, that the Hainan provincial government is in talks to takeover HNA’s $143bn airline to property development business empire.

THE LOCKDOWN CONTINUES TO HAVE MAJOR IMPACT ON THE ECONOMY

It would be nice to believe that the epidemic will have no impact on China’s economy. But common sense tells us this can’t be true. We just have to ask ourselves 5 obvious questions. What would happen to:

- Our own country’s economy, if our capital and a major manufacturing base shutdown for a month?

- Businesses, large and small, if orders stopped and transport was severely disrupted?

- Imports and exports, if critical shipping schedules and flights were cancelled?

- Cash-flow, if the above happened and we still had to pay interest bills on debt?

- Supply chains, if workers at one or more partners couldn’t get to work for a month?

South Korea’s president Moon-Jae has given the obvious answer as the Financial Times reports:

“We should take all possible measures we can think of” to support the economy, Mr Moon told a cabinet meeting on Tuesday. “The current situation is more serious than we thought . . . we need to take emergency steps in this time of emergency.”

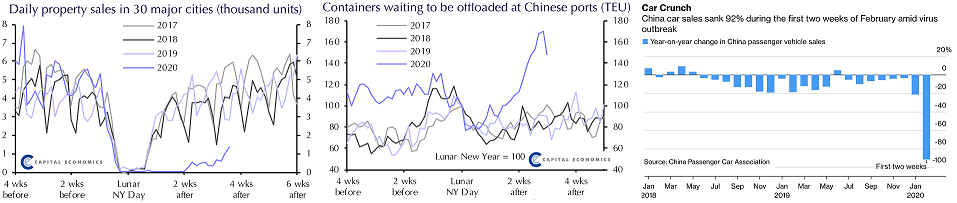

Of course, ‘this time may be different’. But common sense tells us that China’s economy is under enormous pressure today. The charts above highlight the range of areas that are affected:

- Property sales are down 79%, with Evergrande offering 22% discounts through March

- Construction is 25% of GDP, with Fitch identifying 6 developers with high risk of default

- Ports are often at a standstill – and many shippers have simply stopped calling at Chinese ports

- Car sales collapsed by 92% in the world’s largest auto market in the first two weeks of February

5 LIKELY IMPACTS FROM THE LOCKDOWN

1. Domestic sales. Thousands of stores have been shut since the epidemic began, and people are understandably too scared to venture out – even if this was allowed. So we must assume most areas of domestic consumption are being hit.

2. Imports for manufacturing. Chemicals are an excellent guide to the overall position, as the charts show based on Trade Data Monitor data. Given the shipping problems, large volumes of cancelled imports must now be sitting in suppliers’ tanks and warehouses, waiting to find a new market

3. Exports as part of supply chains. Apple’s profit warning highlights how even major companies have been caught out, as they cannot obtain the component supplies on which their global sales depend. Car and electronics companies are probably most at risk, and we will no doubt see more profit warnings as companies realise inventory is running short

4. Domestic suppliers. There is little data available about the virus’ impact on smaller Chinese companies. But presumably many have already gone bust, especially if they were unlucky enough to be in the centre of the downturn, such as those in Hubei and Wuhan

5. Oil and currency markets. Caixin reports that Chinese refinery runs are at just 10mbd, compared to an average 13mbd in 2019:

“The deepening run cuts belie optimism that the impact of the epidemic may have peaked, a sentiment that’s helped spur a recovery in oil prices over the last week and a half. Many people are still trapped in their homes and unable to go to work, while curbs on travel have pummeled demand for transport fuels.”

Currency markets are also realising the worst may yet be to come. Companies such as HNA have been major borrowers in the offshore dollar market – hoping to take advantage of low US interest rates. But as we have seen many times before, when the currency starts to fall, those debts quickly become impossible to service.

A GLOBAL DEBT CRISIS SEEMS ALMOST INEVITABLE

Observers such as myself have warned about this problem for years. Earlier this month, an international G20 task force of currency experts warned:

“Central banks have lost control of global liquidity. The dollarised international financial system has become treacherously unstable and vulnerable to a sudden reversal in capital flows. A decade of ultra-low interest rates and quantitative easing has flooded the globe with highly unstable forms of funding denominated in dollars, with no guarantor standing behind them. Glaring currency and maturity mismatches have accumulated.

“This structure is prone to an abrupt “dollar crunch” should borrowers in China, east Asia, emerging markets, or even parts of Europe suddenly start scrambling for scarce US currency to repay bonds and loans in a crisis.”

Central banks and governments either didn’t realise the risks or, more likely, simply hoped the problem would only hit once they had left the job. But today, this “dollar crunch” may well be about to arrive:

- After a brief rally, the Rmb has gone back below Rmb 7: US$ 1

- This will make it even more impossible for many companies to repay their dollar loans

Many western pension funds felt forced to rush into the offshore dollar market in a ‘search for yield’. Zero rate interest policies meant they couldn’t get the level of yield they needed to fund future pensions in ‘safer’ markets at home. And employers weren’t willing to fill the gap, as this would have hit their earnings and share prices.

Unfortunately, as I noted 18 months ago, Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun also Rises probably describes the end-game we have entered:

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked.

“Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”