Every now and then, people wake up to the fact that debt is only good news when it adds to growth. Otherwise, it simply destroys value.

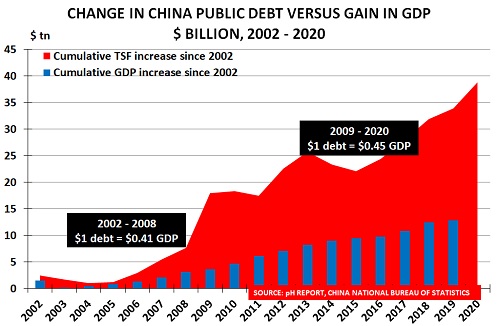

China is usually the case study for this analysis, as the chart confirms. It shows the rise in debt from 2002, when official data begins, versus the rise in debt. One would hope that the borrowing would have had a multiplier impact, creating value. But in reality:

- Debt grew from $2tn in 2002 to $39tn in 2020, as measured by Total Social Financing

- GDP grew from $1.5tn to $13.2tn, according to the National Bureau of Statistics

Even if we leave aside the problems associated with China’s GDP data – uniquely for a major economy, it is reported almost immediately and never revised – we still face one key issue. Each dollar of debt fails to increase GDP by the same amount.

In the 2002-2008 period, each dollar of debt only created $0.41 of GDP growth. Since then, each dollar has created only $0.45c of growth. So the value created by each dollar is less than half the cost of the debt created.

Every now and then, the government gets worried by this state of affairs and tries to do something about it. But it then faces an awkward trade-off as Prof Michael Pettis of Peking University notes:

- Beijing wants as much healthy, sustainable growth as possible. This “‘high-quality’ growth consists mainly of growth generated by consumption, exports, and business investment, with the third closely tracking the first two”

- But it also “relies on fixed-asset investment (FAI) in infrastructure and real-estate development to meet politically motivated growth targets” such as its “above 6% GDP growth target” for 2021

Last year, Beijing panicked during the pandemic and allowed FAI to rise in order to keep GDP growth positive. But the reported GDP growth of 2.3% came with a cost. China’s debt-to-GDP ratio rose from 247% in 2019, to 270% at the end of last year – an astonishing increase.

As a result, Beijing is now planning to cut back on FAI in order to avoid any further increase in the ratio. And it is starting, once again, to tackle the systemic problems in the economy – the speculative real estate bubble, and the problems with hidden local government borrowing.

THE SPECULATIVE REAL ESTATE BUBBLE IS HARD TO CONTROL

I’ve been updating on the bubble for as long as I’ve been writing this blog. And like all speculative markets, it simply gets more and more insane.

I’ve been updating on the bubble for as long as I’ve been writing this blog. And like all speculative markets, it simply gets more and more insane.

I featured this “egg house” as long ago as December 2010 as an example of the way that China’s gender imbalance (117 boys to every 100 girls) gives prospective father-in-laws great leverage when assessing whether the prospective husband can properly support their daughter.

The housing market is around 25% of GDP, and has never been known to fall. As I noted in January 2012, the issue is that until 1998:

“All urban housing was built and allocated by the state. There was no word even for ‘mortgage’, as there was no such thing as private residential property. Even in rural areas, peasants built their homes on land allocated by the state or the collective.

“Another key factor behind the rise in prices has been China’s lack of a proper system of social security. As a result, most women believe owning a home is essential for any man wanting to get married.

“Young bachelors have thus routinely turned to their extended families for help with raising the finance for a home. And as prices were doubling every 2 years over the past decade, the ‘bank of mum and dad, and grandparents, and cousins’ has always been happy to help.

“Equally, the local provinces are dependent on property development for up to 40% of their income”.

LOCAL GOVERNMENT DEBT IS OUT OF CONTROL

A long and detailed analysis in China’s financial paper, Caixin, highlights Beijing’s latest attempt to bring local government debt under control. It notes that:

“A report by Bank of China Ltd. in June said that the hidden debt of local governments likely amounted to Rmb49.3tn ($7.6tn) at the end of 2019, equivalent to nearly half of China’s GDP in 2019.”

The issue, of course, is that this puts the problem in the “too big to fail” category as the director of the Chinese Academy of Fiscal Sciences warns:

“He believes it is reasonable to appropriately restrict the issuance of bonds by LGFVs where local governments have high debt risks. However, implementation must take into account the reality on the ground. If the credit situation of LFGVs deteriorates to the extent that they require large-scale government bailouts, the authorities will need to relax the restrictions, he told Caixin.”

CHINA’S NEW DUAL CIRCULATION PLAN IS THE NEW APPROACH

The key issue is that Chinese private household consumption is only 39% of GDP. Per capita disposable incomes are relatively low, with the national average just Rmb 32k ($4665) in 2020:

In principle, therefore, there is major scope to improve incomes. This is China’s new “Dual Circulation” concept, which is at the heart of the new economic strategy for the coming decades.

It emphasises the role of domestic manufacturing, and the need for China to become ‘master of its own destiny’, by reducing its dependence on imported raw materials and foreign technology.

The aim is make the economy more resilient against external shocks, by tapping into the unexploited potential of China’s huge domestic market and becoming a global leader in cutting-edge technologies.

H1 should see it have an easy introduction, as Beijing focuses on making July’s centenary of the founding of China’s Communist Party a major success. But after that, as the momentum from 2020 reduces, the real challenges will begin.

Will the government really allow growth to slow to its probable ‘natural level’ of 2% – 3%. Or will it feel the need to once again feed the debt machine in order to keep growth humming along?