President Xi’s presence at the Climate Change conference highlights the far-reaching changes set out in China’s new 5 Year Plan, as I describe in my latest post for the Financial Times, published on the BeyondBrics blog

How times change. President Xi Jinping has just become the first Chinese president to attend a climate change conference. His presence in Paris could hardly have been more symbolic of the dramatic shift underway in China, under its New Normal economic policy. After all, it was only six years ago, at the Copenhagen Climate conference, that China’s then premier Wen Jiabao single-handedly wrecked any chance of agreement.

What has caused this dramatic policy turnaround in the world’s second largest economy? One factor is clearly Xi’s oft-stated belief that today’s levels of pollution – and of corruption – represent an existential threat to continued Communist Party rule.

The state-owned China Daily highlighted the pressure at the start of its report on Xi’s Paris speech. It reported:

“The most severe smog hit Beijing on Dec 1st. Air quality and climate change have again become the hot topics in China. More and more people are asking for blue sky.”

But there are more fundamental reasons for the shift, which have so far escaped general notice. Most coverage of China’s new Five-Year Plan (FYP) for 2016 -2020, for example, has focused on the announcement of an end to China’s one child policy. Of course, this is important for people’s personal lives, but in reality it is unlikely to have much impact on China’s population issues. New UN Population Division data shows that China’s current fertility rate of 1.58 babies per woman is exactly in line with that for the whole of Eastern Asia.

The really critical features of the FYP have meanwhile been largely ignored. Yet is it the blueprint for a radical transformation of China’s economy:

- The aim is to move away from the previous model of export-focused growth centred on low-cost manufacturing and vast infrastructure spending

- Instead, Xi aims to stimulate the development of a services-led economy based on the mobile internet

It means an end to stimulus spending of the type that propelled China’s growth, and that of the world economy, after the global financial crisis. And thus it continues the Great Unwinding of stimulus policies, as we discussed back in August.

Instead, the FYP focuses on four key areas – Innovation; Green China; Acceleration of the Opening-Up of China; Continued Reform – and the next stages of the Anti-Corruption Campaign. Its proposals will dominate the government’s programme for the next five years, and identify the priorities for the country’s development. The elevation of Innovation into a strategic priority is particularly striking – never before has it been given such prominence in a FYP. History confirms that these priorities are highly likely to be realised, as the entire governmental system will be focused on their implementation.

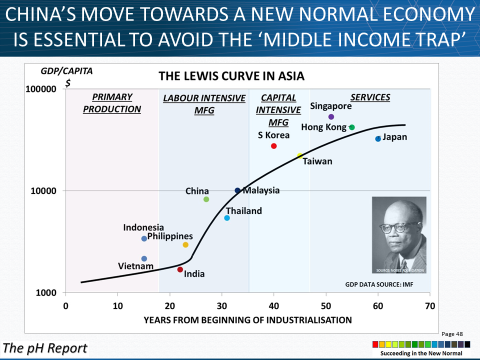

The obvious question is, Why is China attempting such a risky transition, and at a time when the global economy is clearly under-performing? The answer is contained in the chart, which illustrates the road-map developed by Nobel Prizewinner Arthur Lewis to illustrate the four stages of transition from emerging market to developed country status:

Lewis identified what he termed the “middle income trap” which typically hits countries at China’s current stage of development.

- Initially, everything goes well, as emerging economies effectively have a ‘free ride’ in the early years of industrialisation as rural populations move to the towns

- Their contribution to economic growth had been limited in the countryside, focused on planting and harvest seasons. But in cities, they could work 12 hours a day, seven days a week

China’s growth followed Lewis’s model through primary production and labour-intensive manufacturing, as Deng Xiaoping’s reforms began to open up the country to the outside world. Under World Bank guidance, China’s GDP maintained double-digit levels of economic growth, as 278m peasants began the biggest urban migration in history.

But now this ‘free ride’ has ended: China’s ageing population means the workforce has been in decline since 2013. Even if the new population policy did radically increase the birth rate, it would still take 25 years before these babies would enter the 25-to-54-year-old wealth creator cohort, where their spending and earnings would become significant.

Thus China has no choice but to leave behind the Old Normal economy, and instead focus on creating capital-intensive manufacturing and a services-led economy. It is therefore wishful thinking to imagine that the government will undertake new stimulus to revive these areas. Instead, the underlying premise of the innovation drive is an intensifying transition to the New Normal.

As a result, formerly key components of China’s economy such as electricity consumption, bank lending and railcar movements (the so-called “Li Keqiang Index”) are becoming less useful as a proxy measure for Chinese economic growth. Similarly, as we wrote in September, the transition to the New Normal means the global commodities super-bubble is over.

Companies and investors who fail to recognise the criticality of China’s shift to a New Normal economy will face increasingly difficult times in 2016.

Paul Hodges is chairman of International eChem and publisher of The pH Report.